Part 3 - Surviving Democracy

Chicago School dogma became known as Thatcherism in Britain, but its prime minister wasn’t an early adherent. Margaret Thatcher thought Chilean shock therapy wasn’t possible in a democracy like the UK because voters wouldn’t buy it. Three years into her first term, her approval rating was lower than George Bush’s. She was in danger of not being reelected and didn’t dare risk imposing bitter economic medicine that would sink her chances. That is, until destiny intervened on April 2, 1982 when Argentina invaded the British-held Falkland Islands off its coast that was unimportant to either country except for the political hay to gain from war.

She launched a “corporatist revolution” based on Chicago School economics she thought impossible earlier. She parlayed her new popularity to a victory against striking coal miners in 1984 with tactics like unleashing 8000 “truncheon-wielding” riot police in a single confrontation. Before the strike ended, thousands of workers were injured, but Thatcher stood firm with a clear message to other unionists. Take what you’re offered or get the same medicine.

She didn’t stop there, and what followed was a radical economic agenda in a wave of state enterprise privatizations including British Telecom, British Gas, British Airways, British Steel and others in what Klein called “the first mass privatization auction in a Western democracy.” It proved Chicago School fundamentalism didn’t need repressive dictatorships to advance as long as “Iron Ladies” like Thatcher were around to match the best of them, short of all out tanks in the streets shock therapy, that is. Her eleven and a half years in power proved it, and Britain hasn’t been the same since with Labor as committed now as the Tories.

Bolivia was soon targeted as well, but in 1985 was part a democratic wave sweeping the world. It was an election year with two familiar figures facing off for the presidency — former dictator Hugo Banzar and former elected president, Victor Paz Estenssoro. It was close and Banzar thought he won so before final returns were in he named 30 year old Harvard economist Jeffrey Sachs to help develop an anti-inflation economic plan for the country.

Sachs was part Keynsian but larger part Chicago School adherent that made for a bad combination. He bought its orthodoxy in softer form by supporting debt relief and generous aid along with the shock therapy he advised Banzar to adopt as the only solution to hyperinflation.

As it turned out, Banzar lost and Paz won, and while no socialist, he was no Chicago School adherent either, or so voters thought. Four days into his term, he charged his emergency economic team to radically restructure the economy using shock therapy with a twist. It was much harsher than Sachs proposed with the entire state-centered structure Paz erected decades earlier dismantled in the first 100 days before the public could react. In its place, food subsidies were ended, price controls lifted, wages frozen, oil prices hiked 300 percent, deep government spending cuts imposed, unrestricted imports allowed, and state-owned companies downsized as a first step to privatizing them. It cost hundreds of thousands of full-time jobs, pensions and safety net protections. Friedman continued to roll.

The results were predictable. The minimum wage never regained its value, and two years later real wages were down 40 percent and average per capita income dropped from $845 in 1985 to $789 in 1987. As in other shock therapy countries, a small elite got richer while the great majority of Bolivians lost out with campesinos faring worst. In 1987, they earned on average $140 a year, or less than one-fifth the nation’s declining average income.

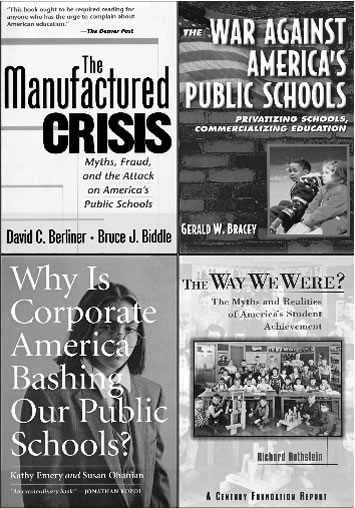

Above photo: During the nearly quarter century since the publication of the Reagan administration’s attack on public school s — “A Nation at Risk” (1983) — the drumbeat of claims that the public schools of the USA had “failed” or were in “crisis” continued. If anything has been constant in the corporate media for the past quarter century — and from politicians from “conservative” to “liberal” — it is the drumbeat of claims about the “failure” of American public schools. Shock treatment — from charter schools and vouchers to the massive "mayoral control" reorganizations ushered in for cities like Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere — has been proclaimed as the only way to save “failing” schools and “failing” school systems.

Above photo: During the nearly quarter century since the publication of the Reagan administration’s attack on public school s — “A Nation at Risk” (1983) — the drumbeat of claims that the public schools of the USA had “failed” or were in “crisis” continued. If anything has been constant in the corporate media for the past quarter century — and from politicians from “conservative” to “liberal” — it is the drumbeat of claims about the “failure” of American public schools. Shock treatment — from charter schools and vouchers to the massive "mayoral control" reorganizations ushered in for cities like Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere — has been proclaimed as the only way to save “failing” schools and “failing” school systems.

Yet every scientific study from the most reputable scholars has shown otherwise. Even in Chicago, those public schools that face the most serious challenges (between 100 and 150 out of 600) are facing conditions in the community that don’t exist outside the Third World and which are invisible to most Americans. Public schools in the USA faces problems, most of which are associated with large areas of poverty, especially in urban and rural America. But almost all studies show that the public schools today are better — and serving a more diverse population — than at any time in history. Beginning with the publication of Berliner and Biddle’s “The Manufactured Crisis” in 1995 (the year that Mayor Daley achieved dictatorial control over Chicago’s public schools), serious scholarly and scientific books like those above and dozens of others — and other studies — have debunked every lie told about the public schools. Other major works depicted on this page include Gerald Bracey's "The War Against America's Public Schools", Susan Ohanian's and Kathy Embry's "Why is Corporate America Bashing Our Public Schools" and Richard Rothstein's "The Way We Were? Myths and Realities of America's Student Achievement." In fact, the number of legitimate (and usually peer reviewed) studies debunking the claims of public school failure since "A Nation at Risk" exceeds by far the corporate propaganda proclaiming that "failure" and posing expenses fixes, which usually involve privatization, deregulation, or some kind of unproven fad for urban poor children that is never implemented for wealthy suburban children.

Yet the lies have become the mainstay of corporate journalism in Chicago and across the country, aided and abetted by publications (from Catalyst to Education Week to much of the daily media) subsidized to provide those lies with what is called "traction" in the jargon of today's punditocracy. Meanwhile, the books refuting the lies, like those mentioned and illustrated here, rarely achieve more than modest sales in the face of the "Shock Doctrine" agendas of the wealthy and powerful.

Bolivian misery gave Sachs star status for the country’s “Miracle.” It launched his new career and brought him to Argentina, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela and Russia later on plus a best-selling book and three-part PBS “success story” series. The only problem was it wasn’t true. President Paz had no mandate for shock therapy, and many workers were predictably furious at his betrayal. They went on strike and Paz’s response made Margaret Thatcher’s earlier action against striking coal miners seem tame by comparison. Tanks rolled in the streets, and riot police raided union halls, a university and factories. Hundreds of arrests followed, including the top 200 union leaders, and oppositional politics was banned. The siege lasted three months during the decisive shock therapy period with more repression and Chicago School medicine later.

It showed shock therapy needs harsh authoritarian rule backing with Bolivia’s pin-stripped politicians, economists and bureaucrats administering it, not uniformed soldiers as in Chile. Paz’s democratic victory was illusory like others when leaders renege on promises and sacrifice them on the alter of Chicago School orthodoxy.

Argentina was another “textbook case.” In the post-Falklands War period, it was burdened with billions in odious debt Washington insisted be serviced and paid. It was far more onerous after the (Paul) “Volker Shock” when the US Federal Reserve Chairman hiked interest rates up to 21 percent in the early-mid 1980s to fight inflation, so he said. It was painful in the US and disastrous for developing countries turning their debt burdens into crises. New loans were needed to pay off old ones, and the debt spiral was born afflicting nations then and still today. That was the whole idea, or at least one of them.

Argentina, Brazil and other countries had another option they didn’t take — defaulting on debt so great it was unrepayable. As Klein put it: “Understandably (new democracies were) unwilling to go to war with Washington (and the international lending agencies it controls so they) had little choice but to play by Washington’s rules (and) in the early eighties (they) got a great deal stricter....It was the dawn of the era of ‘structural adjustment’ - otherwise known as the dictatorship of debt.”

In the 1980s, Chicago School economists colonized the IMF and World Bank to advance their corporatist crusade. Economist John Williamson named it “the Washington Consensus” that stuck ever since. It consisted of core economic policies both institutions consider essential for economic health according to their orthodoxy. We know them well: all “state enterprises ....privatized (and) barriers impeding entry of foreign firms....abolished.” There was more that together was classic Friedman dogma: privatization, deregulation, unrestricted free trade (never called fair), and deep cuts in government spending except for security.

Indebted developing countries learned shock doctrine 101 the hard way. Getting aid meant accepting Washington Consensus rules - the whole package. So to save their countries, they had to “sell (them) off.” Klein calls Argentina the “model student” in the 1990s under leaders like Carlos Menem. Appointing Domingo Cavallo economy minister signaled he bought the corporatist package. But as Klein points out: “Argentina was not unique (and by 1999) Chicago School alumni included more than twenty-five government ministers and more than a dozen central bank presidents from Israel to Costa Rica.”

Shock therapy was on a role that in Argentina turned into a textbook case of therapeutically induced disaster. What Time magazine in 1992 called “Menem’s Miracle” became Menem’s Mirage when the economy collapsed in 2001, and Argentina did the unthinkable with Menem gone and a new president in power. It defaulted on an $805 million debt to the World Bank. It should have ended the neoliberal experiment, but instead it spread. Economic crises fueled it, and when old ones ebbed “even more cataclysmic ones appear(ed): tsunamis, hurricanes, wars and terrorist attacks. Disaster capitalism was taking shape” with shock therapy its tool of choice.