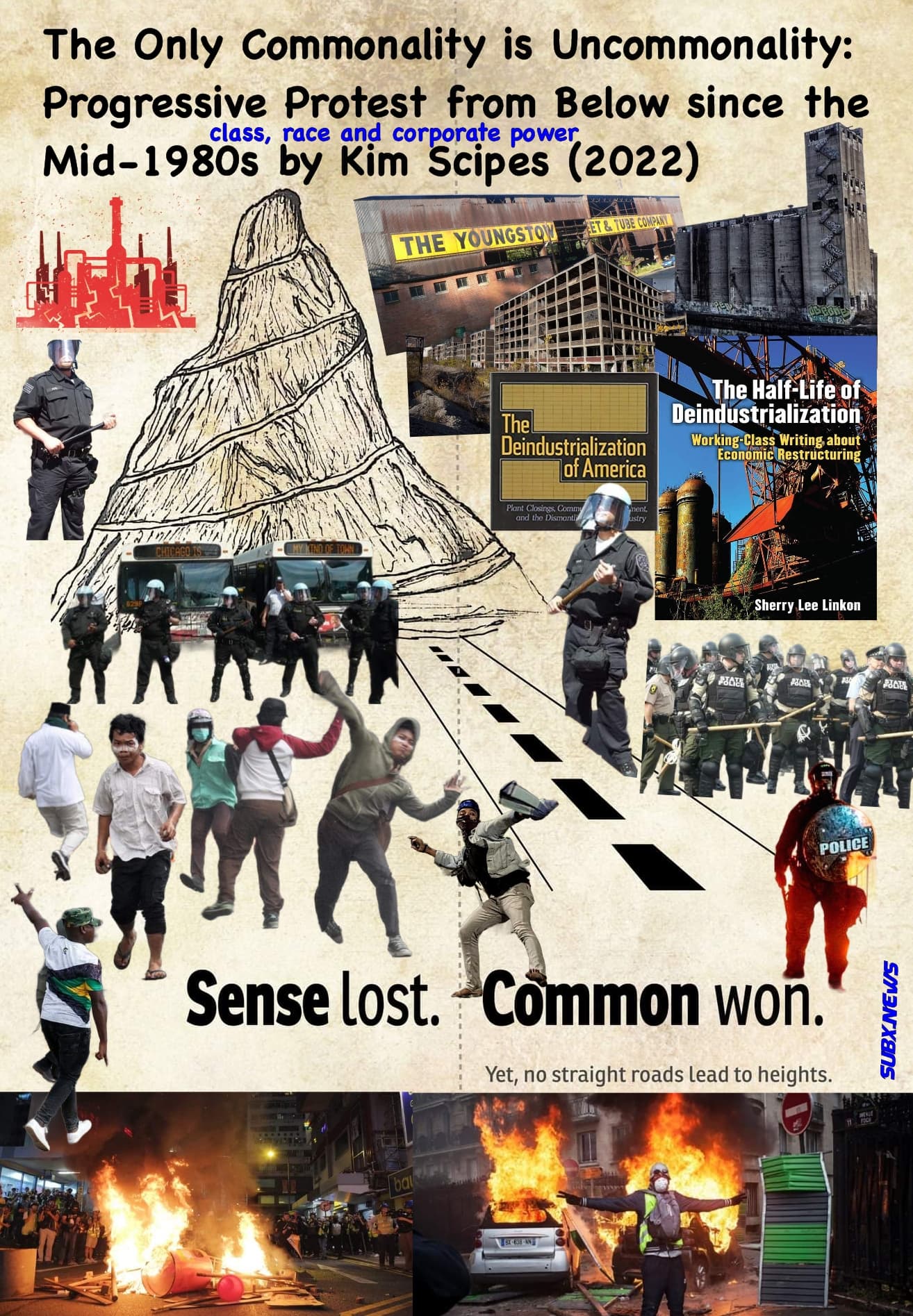

[ Social Unrest Analysis ] The Only Commonality is Uncommonality: Progressive Protest from Below since the Mid-1980s

Scipes, Kim (2022) "The Only Commonality is Uncommonality: Progressive Protest from Below since the Mid-1980s," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol10/iss1/4

Scipes, Kim (2022) "The Only Commonality is Uncommonality: Progressive Protest from Below since the Mid-1980s," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol10/iss1/4

This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact dcc@fiu.edu

Purdue University - North Central Campus, kimscipes@earthlink.net

https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol10/iss1/4/

Class, Race and Corporate Power

Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 4

Abstract

Noting the extensive number of progressive protests, mobilizations, and social disruption from below since the mid-1980s, not just in the US but around the world, this article suggests that what is going on is the expansion of the global economic and social justice movement, a bottom-up form of globalization. It suggests that this is, ultimately, a rejection of industrial civilization itself. And it points out, through an examination of the effects of climate change, that the continued existence of industrial civilization is imposing a burden on the peoples of the world that far outweighs its benefits, and suggests that protests will expand as more and more people understand the costs of industrial civilization.

The world has been and continues to be buffeted by (seemingly) endless protests, mobilizations, and social disruption since the mid-1980s. It is not just taking place in the US, but is happening all over the world.1 How can we make sense of it all?

Challenges to the status quo, the established social order of a number of countries respectively, have been many. The first was the great turmoil in Asia, beginning in the Philippines in 1986 with the expulsion of Ferdinand Marcos from power—the initial “People’s Power” uprising2— and this turmoil extended into South Korea, Burma, Tibet, Taiwan, China (Tiananmen Square), Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia (Katsiaficas, 2012, 2013). And then came 1989 in Eastern Europe, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the dissolution of the Soviet empire (removing the countries of Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, “East” Germany, Poland, and Rumania from Soviet control)3 and, ultimately the Soviet Union itself. And then there was the “fall” of South Africa (Baskin, 1991). In late 1999, there was the “Battle of Seattle,” where protestors blocked the World Trade Organization meetings (Solnit and Solnit, 2009; Thomas, 2000); and these were followed by a number of protests at major political/economic meetings in Quebec, Italy, Cancun, etc. (Starr, 2005). And there was the rebellion within the labor movement in the United States, challenging the AFL-CIO’s foreign policy program (Scipes, 2010a, 2010b, 2012a).4

In between the two waves of upsurge was the emergence and development of the “pink tide” in several Latin American countries, beginning in Venezuela in 1998 with the election of Hugo Chavez as President (Ciccariello-Maher, 2013; Ellner, 2008; Ellner and Hellinger, eds, 2003; Hardy, 2007; Wilpert, 2007). This extended into Bolivia and Ecuador, as well as to other countries of the continent, as people utilized electoral politics to reject the established status quo and seek substantial social change.5 And later, we see social change from below develop in Chile in 2021 (Corrasco Núñez and Daphne, 2022).

The second wave of upsurge began in 2011, with the upsurge in Tunisia, leading to the “Arab Spring,” with rebellion in Egypt, Libya, Syria (Prashad, 2012, and see Moghadam, 2020), and then into Greece, Italy, Spain, and the UK (Castells, 2012; Mason, 2012). But this also includes the uprising in Madison, Wisconsin in early 2011 (Buhle and Buhle, eds., 2011; Nichols, 2012; and Yates, ed., 2012),6 as well as the Occupy Wall Street Movement that spread to over 900 cities and towns across the US and then to over 1500 around the world, along with struggles across North America (Klein, 2014; Jaffee, 2016; Jobin-Leeds, 2016; Smucker, 2017).7 In 2020, protests erupted all across the United States, particularly in response to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis—one estimate is that approximately 26 million people mobilized (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel, 2020) —and in India, millions of farmers and their supporters went on strike in 2020 (Sandhu, 2022).8

Yet throughout this time, working people have been engaged in fights for dignity and social improvement. We see massive protests in countries such as China and India, often around workplace and production-related issues but also challenging environmental devastation (for China, among others, see Chan, Selden, and Ngai, 2020; Ren, ed., 2016; see also Ness, 2016: 107-147; for India, see Sandhu, 2022). Struggles are taking place around the world, in many countries, economic sectors, industries, regions, workplaces, etc. (among others, see Alimahomed-Wilson and Ness, eds., 2018; Buckley, 2021: 86-88; Ness, 2016; Nowak, 2019; O’Brien, 2019; Ovetz, ed., 2020; Scipes, 2018a, 2018b, 2020a, 2020b, 2021).

This is an incredible rebellion by tens if not hundreds of millions of ordinary women and men across the globe, in roughly a 35-year period, protesting the denigration of life, limitations in their material well-being, and/or opposing the destruction of the natural world (see Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert, 2021; Kaufman, 2020), and this spans countries in both the so-called developed and developing worlds. While some expressed their sentiments through voting in electoral projects, most of this turmoil unveiled itself in the streets, and millions have asserted their determination to improve things for themselves and their respective country, and oftentimes with an awareness that it was happening in other countries as well.9

SOMETHING’S HAPPENING HERE:10 WHAT’S GOING ON?

With some idea of these protests occurring around the world, how do we make sense of them: what is going on?

First of all, it must be recognized that much more is going on that has been referred to above; what is mentioned is only some of the protests/mobilizations known, written about, and published. In China, for example,

From the early 1990s, a period of accelerated market-oriented reforms and rapid social change, conflicts multiplied between employees and management. Public security officials began to release statistics on ‘mass incidents’. This all- encompassing category included strikes, protests, riots, sit-ins, rallies, demonstrations, traffic blockades, and other unspecified forms of unrest. The mass incidents ranged widely from protests against unpaid wages and illegal layoffs, to labor and environmental disputes, to religious, ethnic, and political clashes involving workers and other victims who resisted rights encroachment by targeting authority in diverse ways.

The number of mass incidents each year increased from 8,700 in 1993, the first year for which official data is available, to 32,000 in 1999. And the number ‘continued to increase at more than 20 percent a year’ between 2000 and 2003. In 2005, the official record noted 87,000 cases, rising to 127,000 in 2008 during the world recession—the last time the Chinese Ministry of Public Security released figures (Chan, Selden, and Ngai, 2020: 155).

And that’s in only one country.

Interestingly, one of the things that is noted above is that these are not necessarily all related to the same issue. Obviously, there are protests by workers about workplace conditions, pay, and illegal dismissals, but there are also protests around environmental issues, authoritarianism, gender roles/identities, sexuality, religious disputes, etc. So, the “upsurge” is not about the same thing; this is not a “monolithic” protest movement.

Second, these protests are global. They are taking place around the world. They are taking place in imperial and formerly colonized countries—developed and developed countries, in the sanitized terminology of today—and do not seem to be limited to one region or even one continent of the world.

Yet these protests are not all taking place at the same time. Yes, there is some overlap—and in some cases, even some coordination across national borders or even cross-continents (for labor, see Scipes, ed., 2016, and especially Nastovski, 2016, and Dobrusin, 2016; O’Brien, 2019; Scipes, 2021)—so some are taking place at the same time, and sometimes there might be an upsurge like the “Arab Spring” that takes place in a number of different countries about the same time, but there does not seem to be any one thing that triggers the proliferation of protests; there is not one monolithic causal factor.

There is a distinction between “mobilization” and “organization” among protestors and their efforts. Jane McAlevey made the distinction between advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing. She starts off discussing “advocacy,” which is not relevant here, but then she distinguishes between mobilizing and organizing:

Mobilizing … brings large numbers of people into the fight. However, too often they are the same people: dedicated activists who show up over and over at every meeting and rally for all good causes, but without the full mass of their coworkers or community behind them.

…organizing places the agency for success with a continually expanding base of ordinary people, a mass of people never previously involved, who don’t consider themselves as activists—that’s the point of organizing. In the organizing approach, specific injustices and outrage are the immediate motivation, but the primary goal is to transfer power from the elite to the majority, from the 1 percent to the 99 percent. Individual campaigns matter in themselves, but they are primarily a mechanism for bringing hew people into the change process—and keeping them involved. The organizing approach relies on mass negotiations to win, rather than the closed-door deal making typical of both advocacy and mobilizing. Ordinary people help make the power analysis, design the strategy, and achieve the outcome. They are essential and they know it (emphasis added) (McAlevey, 2016: 10).

In other words, while activists have been able to mobilize huge numbers of people at time and have been able to achieve huge short-term affects, because they are usually not organized, these protests cannot be sustained long enough to force large concessions; therefore, almost any upsurge can generally be “ridden-out” by those in power.

And even where people have organized and educated their members—such as in the Philippines (see Scipes, 1996)—limited resources have made it difficult to sustain large-scale mobilizations.

Accomplishments vary. In some cases, such as in the Philippines, Tunisia, and Egypt, dictators were overthrown. In India, reactionary laws were overturned. In other cases, despite often heroic efforts, they were repulsed by the established governments and then dissipated over time (China, Spain, the UK). Some have kept their electoral victories (such as in Venezuela), some have lost their electoral victories (Brazil, Ecuador), some have been denied electoral victories (the UK), and some have seen their liberation efforts undercut by corrupt governmental and/or political party officials (such as in South Africa). Others have seen dictators overthrown, yet replaced with traditional elites (Philippines) or with the established military (Egypt).

In short, the only commonality to all of these efforts is their uncommonality: there certainly does not to appear to be any single causal factor, or even sets of causal factors, that are causing these uprisings.

However, something is going on here. Perhaps we need to approach it from another direction. It is suggested we need to address the term “globalization” to help understand these developments. What we’ve seen in the post-World War II era is a massive explosion in communications, transportation, international travel, violence (both warfare and CIA/NED operations), and a global dispersion of production and consumption. Tied into these factors is a massive increase in synthetic chemical production, and a massive increase in human populations, with human beings now having a greater impact on the planet than natural developments (Angus, 2016), who quotes

One feature stands out as remarkable. The second half of the twentieth century is unique in the entire history of human existence on Earth. Many human activities reach take-off points sometime in the twentieth century and have accelerated toward the end of the century. The last 50 years have without doubt seen the most rapid transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind (emphasis added) (Fred Pearce quoted in Angus, 2016: 38-39).

Covering all of these factors has been a mainstream media that has not critically examined them (see Coteau and Hoynes, 2019).

GLOBALIZATION 11

Globalization is an on-going process. Using the term means taking a planetary scope, no longer restricting one’s analysis to the level of the nation-state (see, for example, McCoy, 2017, 2021; Nederveen Pieterse, 1989). This does not mean that the nation-state is obsolete, irrelevant, etc., but that we cannot confine our political analysis to just the nation-state level. Jan Nederveen Pieterse expands on this:

Among analysts and policy makers, North and South, there is an emerging consensus on several features of globalization: globalization is being shaped by technological changes, involves the reconfiguration of states, goes together with regionalization [for example, European Union, Latin Americanization-KS], and is uneven (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015)12

He further writes that while people oftentimes refer to time-space compression, “It means that globalization involves more intensive interaction across wider space and in shorter time than before” (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015).

Issues Concerning Globalization

There are issues, however, concerning globalization where there are still considerable controversies. Following Nederveen Pieterse, this author argues that in addition to the above, globalization is multidimensional (i.e., cannot be confined to just one aspect, such as economics, but includes things like politics and culture) and should be seen as a long-term phenomenon that began thousands of years ago “in the first migrations of peoples and long- distance trade connections and subsequently accelerates under particular conditions (the spread of technologies, religions, literacy, empires, capitalism” (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015: 70-71). In other words, globalization predates capitalism and modernity, which means it predates the “West.” And, of course, that it did not begin in the 1970s.

While globalization is a much broader, deeper, and longer set of processes than is usually recognized, these processes began accelerating in the early 1970s.

If globalization during the second half of the twentieth century coincided with the ‘American Century’ and the period 1980-2000 coincided with the dominance of Anglo-American capitalism and American hegemony, twenty-first-century globalization shows markedly different dynamics. American hegemony has weakened, the US economy is import dependent, deeply indebted, and mired in financial crises.

The new trends of twenty-first century globalzation are the centers of the world economy shifting to the global South, to the newly industrialized countries, and to the energy exporters (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015: 24).

He further points out these changes are taking place in economic and financial spheres, in international institutions, and in changing patterns of migration. He summarizes that “the unquestioned cultural hegemony of the West is past” (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015: 24-25).

Global development

This argument is an entry into a larger political debate that does not usually recognize, much less acknowledge, the importance of the issue at hand.

The issue is global development. The problem is this: how are the peoples of the world, located in different countries defined as nation-states, and located among a myriad of levels of economic, political, cultural, and social development—hence, this is not an approach centralized on the United States or Europe or even the “Global North” but rather a global approach—going to advance their social well-being, both individually and collectively?

Jan Nederveen Pieterse advances the concept of “critical globalism,” which he defines as the “critical engagement with globalization processes, neither blocking nor celebrating them” (Nederveen Pieterse, 2010: 49). He elaborates:

As a global agenda, critical globalization means posing the central question of global inequality in its new manifestations. As a research agenda, it entails identifying the social forces that carry different transnational processes and examining varying conceptualizations of the global environment and the globalizing momentum….

What, under the circumstances, is the meaning of world development? Because of the combined changes of globalization, informatization, and flexibilization, there is a new relevance to the notion that ‘all societies are developing.’ This is not just an agreeable sounding cliché, but a reality confirmed by transformations taking place everywhere, on macro as well as microlevels. ‘The whole world is in transition’ (Nederveen Pieterse, 2010: 50).

Reflecting On Globalization

While this author agrees with Nederveen Pieterse’s thinking about globalization13—including that it is multidimensional and that it predates modernity—he wants to add another point about globalization: it is multilayered (Scipes, 2012a; Shiva, 2005; Starr, 2005). This is an important point.

Business and governments have appropriated the term “globalization,” insisting that is a monolithic force of good that is deluging the world, and is enveloping all within it, like a wall of flood water that cannot be stopped.

Activists initially responded to this by being against globalization; for instance, Amory Starr’s 2005 book was titled Global Revolt: A Guide to the Movements against Globalization. However, activists came to see that we were not against globalization, but against the type of globalization that was being promoted and propagated (e.g., Friedman, 1999).

A number of authors think a better idea is to recognize that there are two levels of globalization—a top-down, corporate/militaristic globalization, and a bottom-up, global movement for social and economic justice—and that these two levels are based on values completely antithetical to the other (Shiva, 2005). By that, I mean that globalization is not a monolith, a single, collective phenomenon, but it has at least two layers. So, we can refer to as “globalization from above,” and “globalization from below.” What does that mean?

Accepting Nederveen Pieterse’s claim that “globalization involves more intensive interaction across wider space and in shorter time than before” (Nederveen Pieterse, 2015), we must look at the values of each of these levels of globalization. The values of top-down globalization are

those that promote the unhindered spread of capitalist-based corporations around the world, and the militarism (and related wars and military operations) needed to ensure that is possible. In other words, top-down globalization is the latest effort to dominate the world, all living beings and the planet. Accordingly, if one wants to apply the term neoliberal14 to globalization, this refers to only one level of globalization—the top-down level—and thus a particular level of globalization, and that it should not be considered synonymous with globalization as a whole.

Globalization from below, on the other hand, is life enhancing: it rejects domination in all of its forms; seeks to build a new world based on equality, social and economic justice, and respect for all living beings and the planet; and tries to build solidarity among the majority of the world’s peoples (again, see Shiva, 2005; see also Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert, 2021). The two world- views, and the values on which each are based, could not be more opposed.

Thus, understanding that there are two different levels of globalization, and that they are opposed to each other, means that people need to choose: which side are you on?

PEOPLE AND ENVIRONMENT

It appears, however inchoate it may seem today, that we are seeing an expansion of the global economic and social justice movement around the world.15 Let us be clear: except for a relatively small number of activists, for the overwhelming large number of people, this is not necessarily built on a common understanding or conscious direction. Yet when one steps back and tries to understand what is going on, taking into account these planetary-wide events, this seems the most coherent explanation to date.

Yet, is there a common explanation as to why these events are taking place? This author believes so. Though rudimentary, there appears to be an emerging consensus in the process of developing. And that is an increasing rejection of industrial civilization in all of its ramifications (see, among others, Angus, 2016; Hickel, 2022; Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert, 2021; Scipes, 2017).16

What is meant by “industrial civilization”? This is broader than the Marxist conceptualization of capitalism, even in its imperial “stage” (see Lenin, 1916; c.f. Nederveen Pieterse, 1989). In the “Preface” of Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert (2021), one begins to get the idea in the discussion of cities:

Sustainability can be defined as a way of life that doesn’t require the importation of resources. So, if a city requires the importation of resources, it means that city has denuded its landscape of that particular resource. Quite naturally, as a city grows it denudes a larger area; in fact, cities have been denuding countrysides for the past 6,000 years.

Just as a modern city would be impossible without an electrical grid, so is electricity unthinkable without metals being mined to create it. “You can’t take individual technologies out of context,” [Jensen] said, because every system, every object relies upon humans extracting resources from the earth. To make his point, he took off his glasses—[he was debating some “bright green environmentalists” at a public forum and this is an account of the interaction]—and held them up as an example. “They’re made of plastic, which requires oil and transportation infrastructures, and metal, which requires mining, oil, and transportation infrastructures,” he explained. “They’ve also got lenses made of glass, and modern glassmaking requires energy and transportation infrastructures. The mines from which to get the materials to make my reading glasses are going to have to be located somewhere, and the energy with which to manufacture them also has to come from somewhere.

“We need to stop being guided by the general story that we can have it all” [Jensen] concluded, “that we can have an industrial culture and also have wild nature, that we can have an oil economy and still have polar bears” (Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert (2021: xiii-xiv).

Yet, what about arguments that we can capture minerals and redesign things for disassembly— basically that we can recycle our way out of the problem, and basically create a zero-waste, or almost so, economy? Jensen again [from his debate]:

… this idea does not correspond to physical reality. … the process of recycling materials itself requires an infrastructure that is harmful to both the environment and humanity. Not only does the recycling process very often cause more waste and pollution, but it frequently relies upon nearby populations living in unsafe conditions and workers being subjected to both toxins and slave labor (Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert, 2021: xv).17

Another writer, to whose work I’ve just been introduced, is Jason Hickel. Hickel brings a more explicitly global focus to the argument:

You see, capitalist growth in the Global North depends on income suppression in the Global South. 18 This keeps the supply price low and enables capital accumulation. As countries in the Global South increased wages, took control of resources and labor, they deprived the Global North of the access to cheap resource and labor they had enjoyed under colonialism. This shift led to the 1970s crisis of stagflation (low growth and high inflation) in the Global North.

Confronted with this situation, the Global North had two options: either abandon capital accumulation, or try by all means to maintain; it chose the second route. They attacked the unions and cut wages of the working class at home, while imposing structural adjustment programmes across the Global South. In the newly formed republics in the Global South, this backlash reversed progressive reforms, dismantled economic sovereignty, and restored Northern access to cheap Southern resources and labour (emphasis added) (Hickel, 2022).

He then talks about the global ramifications of this within the context of building global solidarity:

A key step is to recognize that in order to maintain the conditions for capitalist accumulation and growth in the Global North, any concessions made to working class demands in the Global North are offset by compressing income and concessions in the Global South as much as possible. Solidarity with the Global South means recognizing this fact and pushing for a post-growth, post-capitalist economy here in the Global North, to remove this brutal pressure. There’s no way around it… (Hickel, 2022).

Now, whether one would take Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert’s argument to its seemingly logical conclusion (they’re actually much more sophisticated thinkers than this suggests) to get rid of all humans and turn the planet back to its animal and natural inhabitants, or Hickel’s—that to build global solidarity, we have to have degrowth immediately in the imperial countries—there is no question that they both make a lot of sense: we must end industrial civilization. Key to this is ending capitalism, while recognizing that, while necessary, this is not sufficient; we must do so much more, such as to eradicate racism, misogyny, war, poverty, imperialism, and all other efforts to dominate human beings, the environment, and the planet, while building a global society based on solidarity and promoting the well-being of the planet and each living being on it (including plants and grasses, fish, and all species).

A major aspect of this, however, is to reject technological “solutions”—Jensen, et. al. (2021) destroy the myth that technology will save all of us—and to realize we must both drastically reduce our individual and systematic assaults on the planet: we must reduce our impact. Period.

What must be understood is capitalism is killing all life on the planet. That means we either have to “kill” capitalism, or be killed by it; it really is key to survival. We have to drastically reduce production at first opportunity, in both the imperial and formerly colonized countries; and we have to drastically reduce the transportation infrastructure—not only transnational shipping (including ships, airplanes, railroads, and trucks), but also private automobiles that carry people to work—that enables it to “work” (see Scipes, 2017). And we must dismantle the fossil fuel infrastructure—oil, coal, natural gas, and nuclear—upon which all of this is based.

We also have to eradicate the systems of empires, world orders, and militarism that play such a major role in extending, maintaining, and/or defending the respective nation-state base for the propagation of empire (McCoy, 2017, 2021).

Now, this is not to deny the benefits provided by industrial civilization as it globalizes from above—particularly provided to many in the imperial countries, and those increasingly provided by a few governments in the “Global South” such as in China to their populations—but the costs to people and the planet are coming to be seen as too expensive, too costly, for the well-being of all. Costs such as war, poverty, immiseration, national debt, etc., extending to a greater and greater extent even in the richest countries, such as the United States (see Scipes, 2009, for a dated, but still pertinent analysis.)19

The greatest cost, however, is to our planetary system and what it means to the survival of our social and environmental worlds. To warn us, scientists have established the concept of “planetary boundaries” (PBs) to warn of increasing threats to the existence of human societies:

The relatively stable, 11,700-year-long Holocene epoch is the only state of the ES [Earth System] that we know for certain can support contemporary human societies. There is increasing evidence that human activities are affecting ES functioning to a degree that threatens the resilience of the ES—its ability to persist in a Holocene-like state in the face of increasing human pressures and shocks.

Two of the PBs—climate change and biosphere integrity—are recognized as “core” PBs based on their fundamental importance for the ES. The climate system is a manifestation of the amount, distribution, and net balance of energy at Earth’s surface; the biosphere regulates material and energy flows in the ES and increases its resilience to abrupt and gradual change. Anthropogenic perturbation levels of four of the ES processes/features (climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, and land-system change) exceed the proposed PBs….

Furthermore,

PBs are scientifically based levels of human perturbation of the ES beyond which ES functioning may be substantially altered. Transgression of the PBs thus creates substantial risk of destabilizing the Holocene state of the ES in which modern societies have evolved. The PB framework does not dictate how societies should develop. These are political decisions that must include consideration of the human dimensions, including equity, not incorporated in the PB framework. Nevertheless, by identifying a safe operating space for humanity on Earth, the PB framework can make a valuable contribution to decision-makers in charting desirable courses for societal development (emphasis added) (Steffen, et. al., 2015).20

The costs can be summarized in one generalized statement that comes from reading a number of sources: if we don’t begin to seriously reduce our carbon dioxide (and equivalent) emissions into the atmosphere by 2030, we’re going to see the beginning of extermination of humans, animals, and most plants by the turn of the century (Scipes, 2017). However, one specific—and as far as known, not challenged, claim—is found in the title of an article published by climate scientist Michael Mann: “Earth Will Cross the Climate Change Threshold by 2036” (Mann, 2014).21

Whether these predictions prove correct or not—something currently unknown could develop/emerge in the future that would challenge these predictions,22 although there is nothing in sight with a reasonable expectation of this—what we know now has been reported by Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021) in their report: “The Physical Science Basis.” From their “Summary for Policymakers,” we see three main conclusions:

• “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere have occurred.” Further, they point out, “Each of the last four decades has been successively hotter than any decade that preceded it since 1850.”

• “The scale of recent changes across the climate system as a whole—and the present state of many aspects of the climate system—are unprecedented over many centuries to many thousands of years.

• “Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. Evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, draughts, and tropical cyclones [hurricanes-author] and, in particular, their attribution to human influence, has strengthened [since the IGCC’s 2015 report].23

In other words, whether the specific predictions prove true or not, the fact is that the impacts of climate change and environmental destruction are increasing, and all expectations are that they will get worse before they get better.

How much worse? In 2003, approximately 2,500 climatologists from 70 nations, writing in the 3rd Assessment of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, predicted that Earth’s median temperature had a 90-99 percent chance of increasing between 1.5-5.8 degrees Centigrade (between 2.5-10.4 degrees Fahrenheit) between 2000-2100. Charles Harper explains:

• A 1.5 degree warming would take us to a climate not experienced since the beginning of agricultural civilization some 6,000 years ago;

• Between 3-5 degrees increase would take us to a climate not experienced by humans since arriving on the earth some 2 million years ago; and

• More than 5 degrees increase would mean a climate not experienced since 40 million years ago, before the evolution of birds, flowering plants, and mammals, and when there were no glaciers in the Antarctic, Iceland, and Greenland (Harper, 2008: 93).

It’s clear that continued warming will not work for anyone.24

CONCLUSION

It seems clear that increasing numbers of people are dissatisfied with how they are being treated in their respective social orders, and they are responding by mobilizing in the streets and the voting booths to challenge the conditions that have been imposed upon them.

That does not mean, of course, that they will be successful in making changes in the immediate to medium-term future; the forces they are challenging have developed over the past 500+ years, and are extremely powerful. Furthermore, leaders of each social order have a good idea of how to defend themselves. Yet these leaders have never faced the fact that they could die along with all of the “ordinary people” if things keep getting worse.

My expectation is that these protests will continue to manifest and intensify, although they will probably ebb and flow over time, and vary in time and place across the globe. Nonetheless, people are dissatisfied, seeking solutions often on their own, but requiring global collective solidarity to address the changes threatening us all.

If this analysis is correct—that capitalist-based industrial civilization is increasingly seen as undesirable by more and more people around the globe—then a conscious understanding has the possibility to move the entire project for human liberation forward at a pace never before seen. We have to reduce the production of greenhouse gases, we have to reduce the production and consumption of planet-based resources, and we must learn to build each other up and not tear each other down. We have to restore the natural, environmental base of each of our societies, and find ways to live harmoniously with nature and with each other. We have to choose life over death.

--------------

notes

1 This author is aware that there have been protests, demonstrations, etc. that have been initiated from the right wing of the political spectrum in the US and around the world. Sometimes, they have even been able to capture the head of state position, such as with Donald Trump in the US, Scott Morrison in Australia, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and Viktor Orban in Hungary. However, I chose to limit my focus herein to the progressive, or life-enhancing efforts that are considered left-of-center.

2 One book that focuses on the organization of workers in the Philippines as a key component of social change, and which presents an overview of the efforts to overthrow Marcos and then discusses workers’ efforts during the succeeding Aquino regime, is Scipes, 1996. For an in-depth examination of the pre-planned coup attempt by a small group of “rebels” to overthrow Marcos, that incompetently required Catholic Church leaders to try to save it and was saved solely by the responses of millions of Filipinos, see McCoy, 1999: 222-258. For a fascinating memoir of a family of activists were who were active in the struggle against Marcos, see Quimpo and Quimpo, 2012.

3 Key to this was the rebellion in Poland; see Bloom, 2014.

4 While much of this rebellion was focused against the AFL-CIO foreign policy program itself, for Fred Hirsch, myself, and some others, it was “to advance the larger project of building international labor solidarity, while seeing the AFL-CIO’s foreign policy program as a major impediment to this larger project” (Scipes, 2010a: 216, endnote #1). For some of the latest writing, specifically trying to develop a theoretical understanding of this larger project— also known as “global” labor solidarity and “transnational” labor solidarity—see Nastovski, 2021, 2022; Scipes, 2016b; 2021.

5 For a critical evaluation of the “pink tide” phenomenon, see Ellner, ed., 2020. This is not to suggest that are no social movements in Latin America; for an excellent overview, see Ronaldo Munck, 2020.

6 For a review of all three books, see Scipes, 2012b.

7 Arguably, the two Presidential campaigns by Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020—especially the former—could be seen as a protest movement, albeit generally limited to electoral politics.

8 While some, like Samir Amin (2017: 113), argue that these rebellions “are closely linked to capitalism,” it is argued here that they are much broader than that; i.e., that while some may be correctly attributed to responses to capitalism, many go way beyond the economic and political relations of capitalism to challenge the entire established social order.

9 George Katsiaficas, following Herbert Marcuse, conceptualized this awareness of grassroots mobilization in other countries and around the world as the “eros effect.” Initially developed to understand the global upsurge by the New Left in the late 1960s-early 1970s (Katsiaficas, 1987), he has now consciously extended it to the rebellions across Asia (Katsiaficas, 2012, 2013).

10 With thanks to Steven Stills.

11 This section on “globalization” is from the “Introduction” to Scipes’ 2016 edited collection, Building Global Labor Solidarity in a Time of Accelerating Globalization: 2-3, 11-12, and 16-17. While this was initially focused on global labor, I am expanding it here to help understand what is happening with people around the world, workers as well as many others.

12 This point about unevenness is very important. It means that these processes affect countries differentially, and they can hit at different times, with different intensities, and so forth. In fact, they can affect different regions in the same countries differentially. In other words, the idea that globalization is a single, monolithic force, sweeping countries at the same time and with the same force, is a myth.

13 For another approach to globalization, writing in the World Systems Theory (WST) paradigm, see Moghadam, 2020. I find Nederveen Pieterse’s approach to be much more sophisticated and useful.

14 Building on the work of Robert Brenner, David Harvey, Frances Fox Piven, Richard Roman and Edur Velasco Arregui, and Jonathan Swarts, Kim Scipes discusses his understanding of neo-liberalism within his analysis of globalization (Scipes, 2016a: 3-10).

15 This author has been studying aspects of these “globalization from below” movements for almost 40 years, with his primary focus on workers and their organizations.

16 Angus (2016) makes a very coherent argument that this should be replaced by “capitalist” civilization, which deserves attention, but as I discuss below, I think the conceptualization of capitalism is too narrow.

17 Jensen, et. al. (2021) spend much of this book examining technological “solutions,” and challenging them.

18 For those unfamiliar with the terms “Global North” and “Global South,” they are short-hand for “developed” and “developing” countries, respectively. The so-called developed countries include those of Western Europe, Canada, the US, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. The developing countries are those of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East.

In reality, all of these terms are euphemisms or “sanitized” words: the more accurate term for the first category is imperial countries, while that for the latter category is formerly colonized countries, although a few colonies still remain, such as Puerto Rico and American Samoa. This terminology more accurately represents their relationships, where the imperial countries colonized through invasion and physical occupation and stole the natural resources, raw materials, and sometimes even their people from those being colonized (regardless of the impact upon their peoples and environment) and took them back to the imperial countries, where they were used to enhance the imperial countries.

19 This analysis, obviously, needs updating, which I hope to do this summer. Nonetheless, the trends identified are still pertinent. To focus on just one aspect, the US National Debt now exceeds $30 TRILLION (Rappeport, 2022), growing $29 trillion since 1981, when it was $ .9 trillion; it was “only” $8.451 trillion (and 64.7 percent of Gross Domestic Product) in 2007, according to the Economic Report of the President, 2007, Table B-1, quoted in Scipes, 2009, and yet the debt burden today is “so large that the government would need to spend an amount larger than America’s entire annual economy in order to pay it off (Rappeport, 2022); i.e., it is over 100 percent of US Gross Domestic Product.

For other indications that life in the United is growing more “tentative”—beginning before the COVID-19 pandemic but continuing—see, for example, DeParle, 2020; Kolata and Taverise, 2019; and Ortaliza, et. al., 2021.

20 For an earlier understanding of the concept of “planetary boundaries, see Foster, Clark, and York (2010: 14).

21 The New York Times reported on the growing number of people who are seeking therapeutic help to help them address their fears that these predictions are likely (Barry, 2022).

22 Jensen, Keith, and Wilbert (2022: 432-460) argue that we would be better served by utilizing natural processes to heal the earth than to rely on technology: for example, they argue, “Stopping deforestation and restoring logged area would remove more carbon dioxide from the air each year than is generated by all the cars on the planet” (p. 438). 23 For an interactive map that illustrates this, see Fountain, Migliazzi and Popovich, 2021; for a related article, see Schultz, 2021. See also Kahn, 2021, for an overall response.

24 For an immediate analysis of what this means for Europe and the world, see Taylor, 2022.

For a provocative projection of what is coming, see McCoy’s Chapter 7, “Climate Change in the Twenty-First Century” in McCoy, 2021: 303-320.

-------------------------------

References

Alimahomed-Wilson, Jake and Immanuel Ness, eds. 2018. Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain. London: Pluto.

Amin, Samir. 2017. “Revolution from North to South.” Monthly Review, Vol. 69, No. 3, July- August: 113-126.

Angus, Ian. 2016. Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Barry, Ellen. 2022. “Climate Change Enters the Therapy Room.” New York Times, February 6.

On-line at https://www.nytimes.com/.../climate-anxiety-therapy.html (accessed on March 17, 2022).

Baskin, Jeremy. 1991. Striking Back: A History of COSATU. New York and London: Verso. Bloom, Jack M. 2014. Seeing Through the Eyes of the Polish Revolution: Solidarity and the Struggle Against Communism in Poland. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Buchanan, Larry, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel. 2020. “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History.” The New York Times, July 3. On-line at https://www.nytimes.com/.../us/george-floyd-protests-crowd- size.html (accessed March 17, 2022).

Buckley, Joe. 2021. “Freedom of Association in Vietnam: A Heretical View.” Global Labour Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2: 79-94. On-line at

https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/globallabour/article/view/4442 (accessed March 17, 2022).

Buhle, Mari Jo and Paul Buhle, eds. 2011. It Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Labor Protest. London and New York: Verso.

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age.

Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Chan, Jenny, Mark Selden, and Pun Ngai. 2020. Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Ciccariello-Maher, George. 2013. We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Corrasco Núñez, Lorena and Jeremy Daphne. 2022. “Chile: A Bright, New World for Women after New Left Wins the Presidency.” February 3. Elitsha News (South Africa). On-line at https://elitshanews.org.za/.../chile-a-bright-new-world... left-wins-the-presidency/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

Croteau, David and William Hoynes. 2019. Media/Society: Technology, Industries, Content, and Users, 6th Ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

DeParle, Jason. 2020. “Hunger Grows Even as Poverty Levels Do Not.” New York Times, July 29: A-4. On-line, with a slightly different title, at https://www.nytimes.com/.../coronavirus-hunger-poverty.html (accessed March 17, 2022).

Dobrusin, Bruno. 2016. “Labor and Sustainable Development in Latin America: Re-building Alliances at a New Crossroads” in Scipes, ed.: 103-120.

Ellner, Steve. 2008. Rethinking Venezuela’s Politics: Class, Conflict, and the Chavez Phenomenon. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Ellner, Steve, ed. 2020. Latin America’s Pink Tide: Breakthroughs and Shortcomings. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Ellner, Steve and Daniel Hellinger, eds. 2003. Venezuelan Politics in the Chávez Era: Class, Polarization and Conflict. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Foster, John Bellamy, Brett Clark, and Richard York, 2010. The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Fountain, Henry, Biachi Migliazzi, and Nadja Popovich. 2021. “A Global Tour of a Record-Hot Year.” New York Times, January 15. On-line, with a slightly different title, at https://www.nytimes.com/.../cli.../hottest-year-2020-global- map.html (accessed March 17, 2022)

Hardy, Charles. 2007. Cowboy in Caracas: A North American’s Memoir of Venezuela’s Democratic Revolution. Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Press.

Harper, Charles L. 2008. Environment and Society: Human Perspectives on Environmental Issues, 4th Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Hickel, Justin. 2022. “Degrowth is About Global Justice.” Green European Journal, January 5.

On-line at http://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/degrowth-is-about.../ (accessed on March 17, 2022.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2021. “The Physical Science Basis: Summary for Policymakers. On-line at https://www.ipcc.ch/.../report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf (accessed March 17, 2022).

Jaffe, Sarah. 2016. Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt. New York: Nation Books.

Jensen, Derrick, Lierre Keith, and Max Wilbert. 2021. Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It. Rhinebeck, NY: Monkfish Book Publishing Co.

Jobin-Leeds, Greg and AgitArte. 2016. When We Fight, We Win! Twenty-First Century Social Movements and the Activists That are Transforming Our World. New York: The New Press.

Kahn, Brian. 2021. “The Scientists Are Terrified.” November 1. On-line at https://gizmodo.com/the-scientists-are-terrified-1847973587 (accessed March 17, 2022).

Katsiaficas, George.

--- 1987. The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968. Boston: South End Press.

--- 20l2. Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, Vol. 1: “South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century.” Oakland: PM Press.

--- 2013. Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, Vol. 2: “People Power in the Philippines, Burma, Tibet, China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia.” Oakland: PM Press.

Kaufman, Cynthia. 2021. The Sea is Rising and So Are We: A Climate Justice Handbook. Oakland: PM Press.

Klein, Naomi. 2014. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kolata, Gina and Sabrina Tavernise. 2019. “It’s Not Just White People Driving a Decline in Life Expectancy.” New York Times, November 27: A-1. On-line at https://www.nytimes.com/.../life-expectancy-rate-usa.html (accessed March 17, 2022).

Lenin, V.I. 1916. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. New York: International Publishers.

Mann, Michael E. 2014. “Earth Will Cross the Climate Danger Threshold by 2036.” Scientific American, April 1. On-line at https://www.scientificamerican.com/.../earth-will-cross... threshold-by-2036/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

Mason, Paul. 2012. Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions. London and New York: Verso.

McAlevey, Jane F. 2016. No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

McCoy, Alfred W.

--- 1999. Closer than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Military Academy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

--- 2017. In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of US Global Power. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

--- 2021. To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2020. Globalization and Social Movements, 3rd Edition: “The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives.” Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Munck, Ronaldo. 2020. “Social Movements in Latin America: Paradigms, People, and Politics.”

Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 47, No. 4, July: 20-39.

Nastovski, Katherine.

--- 2016. “Worker-to-Worker: A Transformative Model of Solidarity—Lessons from Grassroots International Labor Solidarity in Canada in the 1970s and 1980s” in Scipes, ed.: 49-77.

--- 2021. “Assessing the Role of Transnational Labor Solidarity Within the Broader Struggles for Workers’ Justice.” Global Labour Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, May: 113-330. On-line at https://mulpress.mcmaster.ca/globallabour/article/view/4042 (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2022. “Transnational Labour Solidarity and Question of Agency: A Social Dialectical Approach to the Field.” Labor History, February. On-line at https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2022.2045262 (accessed March 17, 2022).

Nederveen Pieterse, Jan.

--- 1989. Empire and Emancipation: Power and Liberation on a World Scale. New York: Praeger.

--- 2010. Development Theory: Deconstruction/Reconstructions, 2nd Ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

--- 2015. Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange, 3rd Ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Ness, Immanuel. 2016. Southern Insurgency: The Coming of the Global Working Class. London: Pluto Press.

O’Brien, Robert. 2019. Labor Internationalism in the Global South: The SIGTUR Initiative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ortaliza, Jared, Giorlando Ramirez, Venkatesh Satheeskumar, and Krutika Amin. 2021. “Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker: How Does US Life Expectancy Compare to Other Countries?” September 28. On-line at https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart- collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

Ovetz, Robert, ed. 2020. Workers’ Inquiry and Global Class Struggle: Strategies, Tactics, Objectives. London: Pluto Press.

Quimpo, Susan F., and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo. Subversive Lives: A Family Memoir of the Marcos Years. Metro Manila: Anvil Publishing Co.

Rappeport, Alan. 2022. “US National Debt Tops $30 Trillion as Borrowing Surged Amid Pandemic.” New York Times, February 2: A-1+. On-line at https://www.nytimes.com/.../national-debt-30-trillion.html (accessed on March 17, 2022).

Ren, Hao, ed. 2016. China on Strike: Narratives of Workers’ Resistance. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Sandhu, Amandeep. 2022. “How India’s Farmers Launched a Movement Against Modi’s Farm Bills—and Won.” Countercurrents.org, January 31. On-line at https://countercurrents.org/.../how-indias-farmers... modis-farm-bills-and-won/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

Schultz, Isaac. 2021. “Ground Temperatures Hit 118 Degrees in the Arctic Circle.” Gizmodo, June 22. On-line at https://portside.org/2021-06-28/ground-temperatures-hit-118- degrees-arctic-circle (accessed March 17, 2022).

Scipes, Kim.

--- 1996. KMU: Building Genuine Trade Unionism in the Philippines, 1980-1994. Quezon City: New Day Press. (On-line, in entirety, for free at https://www.pnw.edu/faculty/kim- scipes-ph-d/publications/ below the books; accessed March 17, 2022.)

--- 2009. “Neo-Liberal Economic Policies in the United States: The Impact of Globalization on a ‘Northern’ Country.” Indian Journal of Politics and International Relations, Vol. 2, No. 1, January-June: 12-47. On-line at https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/neo-liberal- economic-policies-in-the-united-states-by-kim-scipes-1/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2010a. AFL-CIO’s Secret War against Developing Country Workers: Solidarity or Sabotage? Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

--- 2010b. “Why Labor Imperialism? AFL-CIO’s Foreign Policy Leaders and the Developing World.” Working USA, Vol. 13: 46-479.

--- 2012a. “Globalization from Below: Labor Activists Challenging the AFL-CIO Foreign Policy Program.” Critical Sociology, Vol. 38, No. 2: 303-323. On-line at https://www.researchgate.net/.../254084376_Globalization...

_Activists_Challenging_the_AFL-CIO_Foreign_Policy_Program (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2012b. “A Look Back at the Wisconsin Uprising: A Review Essay of It Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the New Labor Protest, ed. by Mari Jo Buhle and Paul Buhle; Uprising: How Wisconsin Renewed the Politics of Protest, from Madison to Wall Street by John Nichols; and Wisconsin Uprising: Labor Fights Back, ed. by Michael D. Yates.” Z Net, July 18. [Republished February 16, 2017 and on-line at www.substancenews.net/articles.php?page=6674 (accessed March 17, 2022.]

--- 2016a. “Introduction” to Scipes, ed., 2016: 1-21. On-line at https://www.academia.edu/.../INTRODUCTION_to_Scipes_ed...

_Labor_Solidarity (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2016b. “Multiple Fragments—Strength or Weakness? Theorizing Global Labor Solidarity” in Scipes, ed., 2016: 23-48. (This can be downloaded at https://www.researchgate.net/.../315617986_Multiple... Strengths_or_Weaknesses_Theorizing_Global_Labor_Solidarity (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2017. “Addressing Seriously the Environmental Crisis: A Bold, “Outside of the Box” Suggestion for Addressing Climate Change and other Forms of Environmental Destruction.” Class, Race and Corporate Power, Vol. 5, Iss. 1, Article 2. On-line at https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorpo.../vol5/iss1/2 (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2018a. “I Read the News Today, Oh Boy!” Z Net, August 4. On-line at https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/i-read-the-news-today-oh-boy/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2018b. “Another Type of Trade Unionism IS Possible: The KMU Labor Center of the Philippines and Social Movement Unionism.” Labor and Society, Vol. 21: 349-367.

--- 2020a. “The AFL-CIO’s Foreign Policy Program: Where Historians Now Stand.” Class, Race and Corporate Power, Vol. 8, Iss. 2, Article 5. On-line at https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorp.../vol8/iss2/5/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2020b. “Regional Aspirations with a Global Perspective: Development in East Asian Labour Studies.” Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 52, No 11: 1214-1224. https://www.researchgate.net/.../341719609_Regional... al_perspective_Developments_in_East_Asian_labour_studies (accessed March 17, 2022).

--- 2021. Building Global Labor Solidarity: Lessons from the Philippines, South Africa, Northwestern Europe, and the United States. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Scipes, Kim, ed. 2016. Building Global Labor Solidarity in a Time of Accelerating Globalization. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Scott, James. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Smucker, Jonathan Matthew. 2017. Hegemony How-To: A Roadmap for Radicals. Oakland: AK Press.

Solnit, David, and Rebecca Solnit. 2009. The Battle of the Story of The Battle of Seattle. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Starr, Amory. 2005. Global Revolt: A Guide to the Movements against Globalization. London and New York: Zed Press.

Steffen, Will, et. al. 2015. “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.” Science, February 13, Vol. 347, Issue 6223. On-line at https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1259855 (accessed March 17, 2022).

Taylor, Clare. 2022. “Adapt or Else: What the Latest IPCC Report Means for Europe and the World.” Green European Journal, March 16. On-line at https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/adapt-or-else-what... for-europe-and-the-world/ (accessed March 17, 2022).

Thomas, Janet. 2000. The Battle in Seattle: The Story Behind and Beyond the WTO Demonstrations. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishers.

Wilpert, Greg. 2007. Changing Venezuela by Taking Power: The History and Policies of the Chávez Government. London and New York: Verso.