George Schmidt's life of love and service

[This article was originally published on Oct. 6, 2018.]

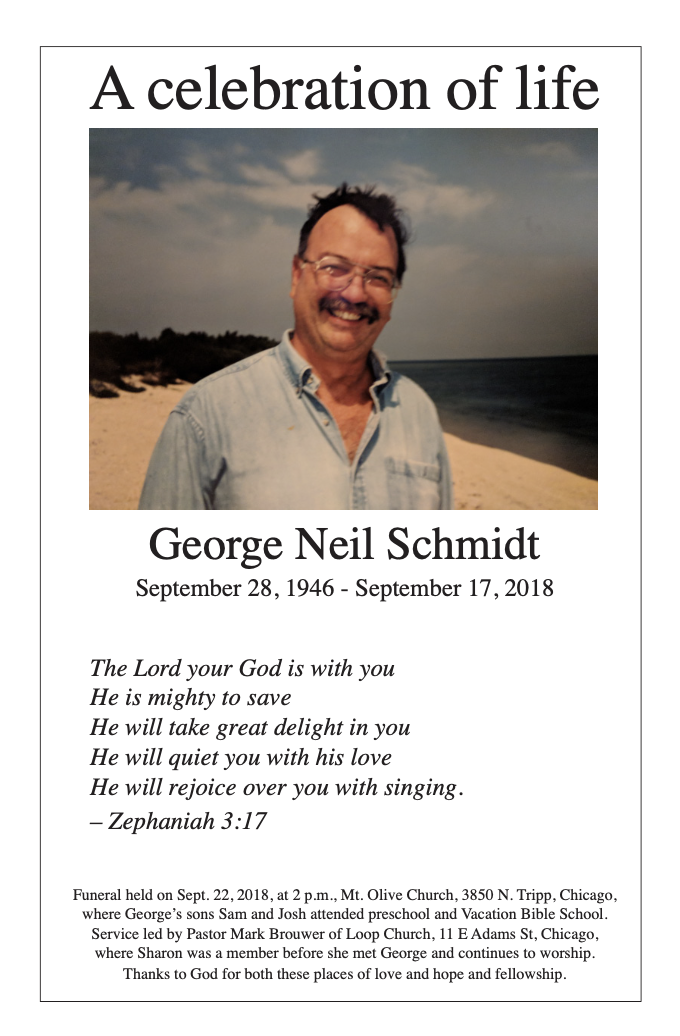

George Neil Schmidt's life was filled with his deep love of family and friends and an intense calling to serve humanity. He was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on Sept. 28, 1946, and died in his home in Chicago on Sept. 17, 2018, at age 71. He was my husband of 20 years, and the father of Daniel Cornelius Schmidt (29), Samuel George Schmidt (17) and Joshua Griffin Schmidt (13). (Ages of sons at George's death).

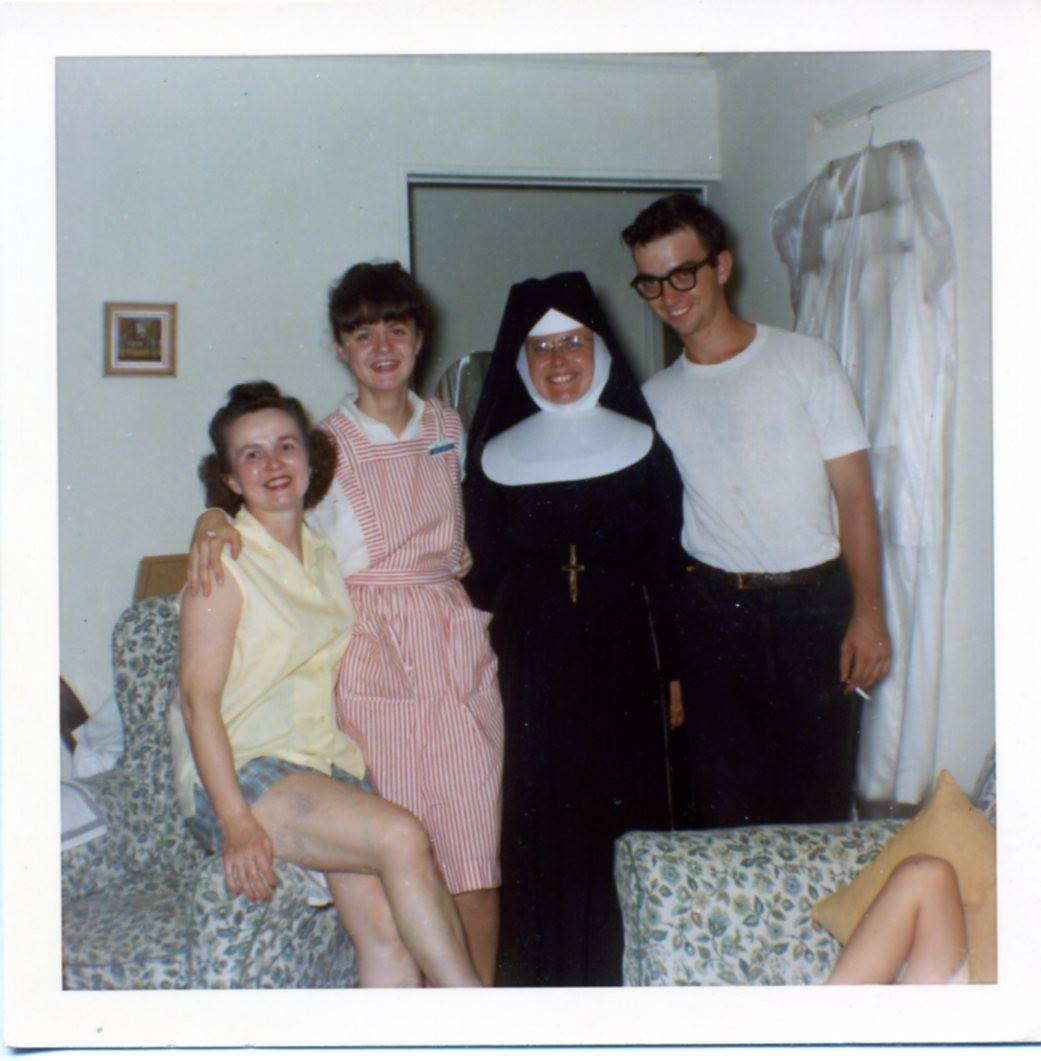

Visiting Linden Park in his New Jersey hometown.

Visiting Linden Park in his New Jersey hometown.

He served many thousands of people – students in some of Chicago’s poorest schools, who received his inspired teaching of literature and writing; workers, who saw their salaries, conditions and voices strengthened through George’s union work, as he served as delegate, mentor, consultant and researcher; and readers of his reports and commentary in Substance and other publications, who found true stories and analysis that never would have been told by corporate media.

Although George had some tough times, including chronic back pain that began in his late 50s, he was grateful for all the years of his life.

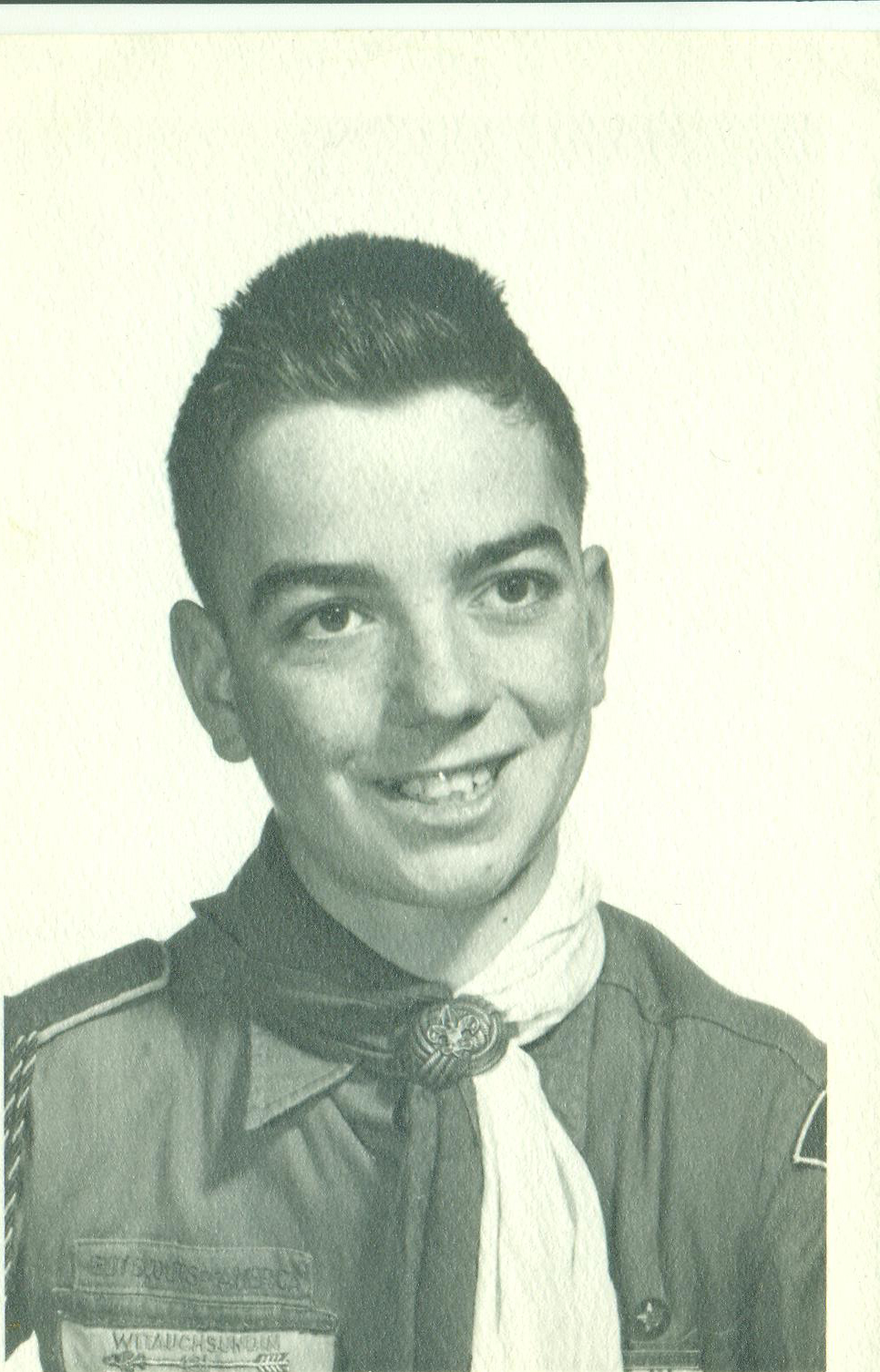

George followed the example and teaching of his parents, Neil Schmidt and Mary Schmidt, both WW II veterans. Picture shows George receiving Eagle Scout award at age 13.

George followed the example and teaching of his parents, Neil Schmidt and Mary Schmidt, both WW II veterans. Picture shows George receiving Eagle Scout award at age 13.

Raised to serve others

George was raised in Linden, New Jersey, at a time when service to the country was highly respected. As were nearly all the adult males on his block, his parents were World War II veterans – his father Neil fought as an infantry soldier in Europe and his mother Mary served in the Army Nurse Corps on Okinawa, Japan. George said his interest in justice and democracy began when he was young, listening to the stories of his family about poverty during the Great Depression and battles against Nazism and imperialism.

George always honored his parents, Mary and Neil, who died in 1985 and 1995. Without them, he honored my parents – Em and Jean Griffin. He respected intellectual and creative gifts, strong values and virtuous lives. He also honored them simply because that’s the right thing to do, to honor your parents.His mother Mary, who after the war continued to work part time as a nurse, and his father Neil, who worked in the post office, taught George and his younger brother Tommy and younger sisters Joan and Terry to value hard work, education and fairness. Throughout his life, George honored his parents and these values.

George always honored his parents, Mary and Neil, who died in 1985 and 1995. Without them, he honored my parents – Em and Jean Griffin. He respected intellectual and creative gifts, strong values and virtuous lives. He also honored them simply because that’s the right thing to do, to honor your parents.His mother Mary, who after the war continued to work part time as a nurse, and his father Neil, who worked in the post office, taught George and his younger brother Tommy and younger sisters Joan and Terry to value hard work, education and fairness. Throughout his life, George honored his parents and these values.

George at 13.“My parents placed education and understanding in front of material things and insisted that their children share those same values,” George wrote in a letter to me (in 2007). “The ideas that a human society should be governed by commercial and financial greed was almost incomprehensible to them, and I think that was based on what they had seen firsthand in their own lives and during the war they helped win.”

George at 13.“My parents placed education and understanding in front of material things and insisted that their children share those same values,” George wrote in a letter to me (in 2007). “The ideas that a human society should be governed by commercial and financial greed was almost incomprehensible to them, and I think that was based on what they had seen firsthand in their own lives and during the war they helped win.”

George always honored his parents, and as a side note, without them (as they died in the 80s and 90s), he honored my parents. He respected intellectual and creative gifts, strong values and virtuous lives. He also honored them simply because that’s the right thing to do, to honor your parents.

Like his father, George was gifted with intellectual curiosity and abilities. He was his kindergarten’s valedictorian. His voracious reading and prolific writing began as a child. He excelled academically. He also embraced scouting, rising to Eagle Scout as a 13-year-old.

“Among the neighborhood kids and school and boy scouts, George was always the very creative leader,” his brother Thomas Lanigan Schmidt wrote. “George, me and a small group of other kids used to go on all-day-long hikes from Linden to the Staten Island zoo. Amazing, that he had such a strong sense of leadership qualities at such a young age (12ish), to walk from Linden across the Goethals Bridge and then all the way across Staten Island to the zoo.”

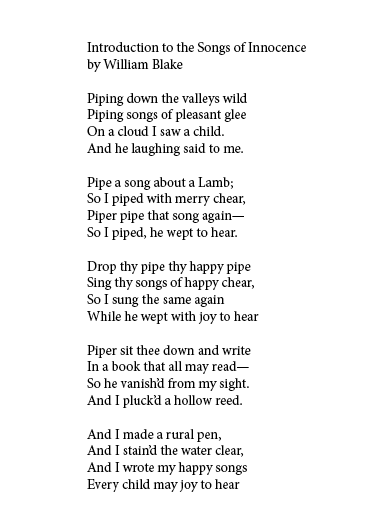

George Schmidt, right, at age 13, with younger siblings Tom, Terry, and Joan. George and Tom were alter boys at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Linden, New Jersey.The brothers served as alter boys at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Linden. Tommy told me they knew how to pray in Latin back then. George helped the family financially, as did his siblings. He worked a daily paper route for the Newark Star Ledger from age 12 until he left home for college. Every day, except Sunday, George prepared the papers and biked his route. On Sundays, because the edition was too big for his usual one or two trips on his bike, his father drove him.

George Schmidt, right, at age 13, with younger siblings Tom, Terry, and Joan. George and Tom were alter boys at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Linden, New Jersey.The brothers served as alter boys at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Linden. Tommy told me they knew how to pray in Latin back then. George helped the family financially, as did his siblings. He worked a daily paper route for the Newark Star Ledger from age 12 until he left home for college. Every day, except Sunday, George prepared the papers and biked his route. On Sundays, because the edition was too big for his usual one or two trips on his bike, his father drove him.

George with his mother Mary and siblings Joan, Terry and Tommy.

George with his mother Mary and siblings Joan, Terry and Tommy.

George's childhood creativity

By Terry Schmidt - October 05, 2018

When George and Tom were younger, they would build things together – a “fun house” and an igloo. They needed someone to test those on, and because I was so little, it was me. “Oh boy my big brothers want me to play with them,” I’d think. So they built a fun house (more like a house of horrors), put me in a milk box, and moved me up and down tracks made from fence posts, having me go through tunnels, tossing boards with nails in them at me, not to be mean, just testing it out. As Tommy later said, I wasn’t hurt.

George in Linden in the early 1950s.After a snowstorm, they built an igloo. To ensure its somewhat stability, they made ice atop it, decided to test it. They told me to sit inside the igloo all the way toward the back. Again, “Oh boy, my big brothers want me to play with them.” They jumped up and down on it (I kept hearing the thuds). Luckily it never caved in. Strangely I never felt fear. Our mother called us in for a Campbell’s chicken noodle soup lunch to warm up (unaware of my precarious status), and that was that.

George in Linden in the early 1950s.After a snowstorm, they built an igloo. To ensure its somewhat stability, they made ice atop it, decided to test it. They told me to sit inside the igloo all the way toward the back. Again, “Oh boy, my big brothers want me to play with them.” They jumped up and down on it (I kept hearing the thuds). Luckily it never caved in. Strangely I never felt fear. Our mother called us in for a Campbell’s chicken noodle soup lunch to warm up (unaware of my precarious status), and that was that.

George always loved music, and for those who remember the song “The Slop,” he could dance. Once he and his teenage friends had a “beatnik” party in our basement. Some had bongos, all wearing sunglasses, listening intently to songs, such as “Midnight in Moscow” and “Walk Don’t Run.” I, in my 11-years-old or so self, sat on the cellar steps in awe of teenagers, until George chased me up the stairs.

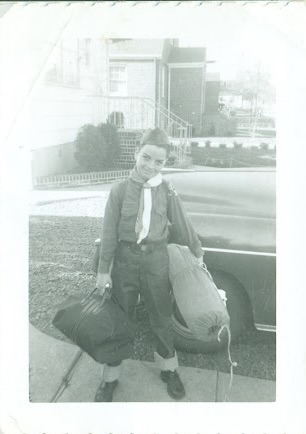

A Blake poem George loved to recite at age 14.

A Blake poem George loved to recite at age 14.

George's deep, happy joy

By Thomas Lanigan Schmidt - September 16, 2018 An important memory of George in the 9th grade suddenly popped into my mind this morning at about 4 a.m. [the day before George died].

He was new at St. Benedict’s prep at the time. Sometimes, just before bedtime (we slept in the attic room), George would stand up and recite poems that he must’ve memorized because he wasn’t reading them from a book. The poems that he loved to recite the most were by William Blake from “Songs of Innocence.” The poem that began with these lines: Piping down the valleys wild, Piping songs of pleasant glee

On a cloud I saw a child.

And he laughing said to me.

Blake is the poet that meant so much to him while he was beginning to enter adulthood. He loved those Blake poems very, very, very much. He would get an expression of deeply happy joy when reading Blake out loud.

With his mom, his younger sister Joan, and an aunt.

With his mom, his younger sister Joan, and an aunt.

Sharing his love of literature

By Joan Schmidt - October 8, 2018

George’s desire to impart knowledge to others manifested itself when he was a teenager. He would leave the books he was reading – Dickens, Dostoevsky, Eugene O’Neill – on the dresser outside my bedroom, then he would encourage me to read them and discuss them with me afterwards. His enthusiastic ability to help foster my love of literature is one of the things I loved about him. I will miss him very much.

George with girlfriend Sheila Dorsey (at left) before prom in June 1964.

George with girlfriend Sheila Dorsey (at left) before prom in June 1964.

George's development and exploration during his teen years — truth and beauty in literature, friendships, romance

As a teen, George began exploring nearby New York City, taking the train into the city to go to the 8th Street Bookstore. He loved poetry and great works of literature. His sister Terry and cousin Mary Lanigan Regan told Substance about a “beatnik party” George hosted in 1964.

“There was an admission fee for the party – one poem you had written yourself,” Mary said. “Many of the guests got up and read their poems, and the audience responded with the ‘applause’ of finger-snapping. It must have been the early summer of 1964, because George and I had just graduated from high school and I remember my poem was about the JFK assassination.”

George’s brother added the following: “There were lots of different people reading poems that they composed. Lots of people wearing berets too. And my mother checking every now and then to make sure that nobody was misbehaving. There were always clothes or towels drying on the clothes line ropes on the other side of the basement, so my mother could always create a plausible subterfuge for running up and down the cellar stairs. "She was very emphatic that she did not want a teenage make-out-party happening in a good Catholic home. It was a very creative bunch of teenagers. Most were George’s friends from St.Benedict’s prep in Newark.”

George dated several young women, especially Sheila Dorsey, who was one year older than him and used to pick him up outside his high school in her convertible. He had friends from his school in Newark and a best friend in the neighborhood, Maurice O’Callaghan. Beginning in his early teens, George lifted weights and competed in Olympic-style weightlifting events. As a child, and throughout his life, George was strong – physically, emotionally, intellectually – the one who would stand up to bullies.

He was educated in Catholic schools, attending elementary school at. He obtained scholarships to St. Benedict’s Preparatory High School in Newark and to St. Vincent’s College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, to study study history, poetry, and philosophy. After two years at St. Vincent’s, where he felt the academics weren't strong enough, George received a scholarship to the University of Chicago.

Mary Schmidt was a second lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corp, stationed with the 86th evacuation hospital in Okinawa, Japan from April to September 1945.

Mary Schmidt was a second lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corp, stationed with the 86th evacuation hospital in Okinawa, Japan from April to September 1945.

Understanding the horror of war

As a child, George played with his cousins and the children on his block, swam at the Linden pool and took occasional family trips to the beach and Coney Island, led by his mother. He remembered her creativity, joyful celebrations, and love for him and his family. His brother, who is now a well known artist, said their mother was a creative genius.

Neil Schmidt was drafted into the 44th division of the Army in 1940. He fought in Europe from October 1944 through May 1945.But George’s childhood – which included the hope of his parents’ post-war generation – was also colored by his mother’s depression, psychosis, suicide attempts and hospitalizations, beginning when he was 14. It was right at that same time period when George was reciting poems from Blake’s "Songs of Innocence" that he saw his mother in the early morning after her first suicide attempt. George said her anguish was caused in part by post traumatic stress from her years working in a combat zone.

Neil Schmidt was drafted into the 44th division of the Army in 1940. He fought in Europe from October 1944 through May 1945.But George’s childhood – which included the hope of his parents’ post-war generation – was also colored by his mother’s depression, psychosis, suicide attempts and hospitalizations, beginning when he was 14. It was right at that same time period when George was reciting poems from Blake’s "Songs of Innocence" that he saw his mother in the early morning after her first suicide attempt. George said her anguish was caused in part by post traumatic stress from her years working in a combat zone.

“It wasn’t until years later and after I had been counseling soldiers back from Vietnam that I realized the problems my mom had came from her experiences in the field hospital in Okinawa,” George wrote to me in a letter. “But in those days the country didn’t have much of a way of dealing with women who had experienced firsthand the horrors of combat. My mom was just left out there by a country in denial, officially at least, about what war really was and did. She had nightmares the rest of her life.”

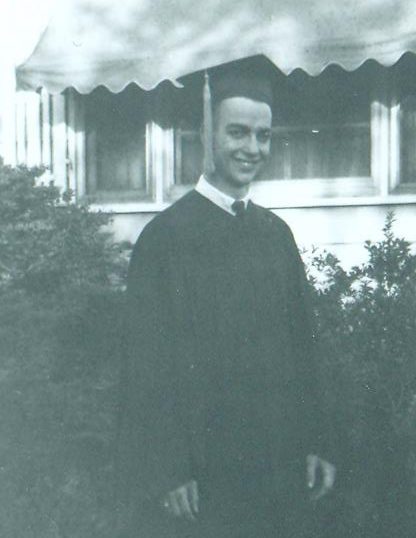

George graduated St. Benedict's High School (Newerk, NJ) in 1964.

George graduated St. Benedict's High School (Newerk, NJ) in 1964.

Protesting the Vietnam War and racial injustice at college

In 1965, during George's second year at college, George first met people who opposed the Vietnam War. Tom Cornell, one of the first Catholic conscientious objectors and draft card burners, visited St. Vincent College during a series of anti-war events and stayed in George’s dorm room. George said his courage impressed him.

George was also moved then and throughout his life by the horrors of racial injustice. His first demonstration came on behalf of the Westmoreland County NAACP in Jeanette, Pennsylvania, protesting racial discrimination. In a May 21, 1966, letter he wrote to his cousin Mary, George talked about some of the protest work he was doing at his small college in Pennsylvania: “This year was the beginning of our Berkeley here. I became a politician and polemicist. I edited a subversive student magazine … the last issue went after one of the kings of the monastery, a Thomistic poli-sci teacher who believes people and the world stopped growing in the fourteenth century. We’re getting to him, even. Meanwhile, there’ve been protest marches, faculty walkouts, writing for all kinds of things … The last thing on every list has been, unfortunately, studies.”

In the letter he talks about the English and German literature courses he liked, as well as Metaphysics, impressed that “our prof is a philosopher, not just a philosophy teacher.” But George was frustrated with the weak academics of the small college and happy to be moving on from Catholic education.

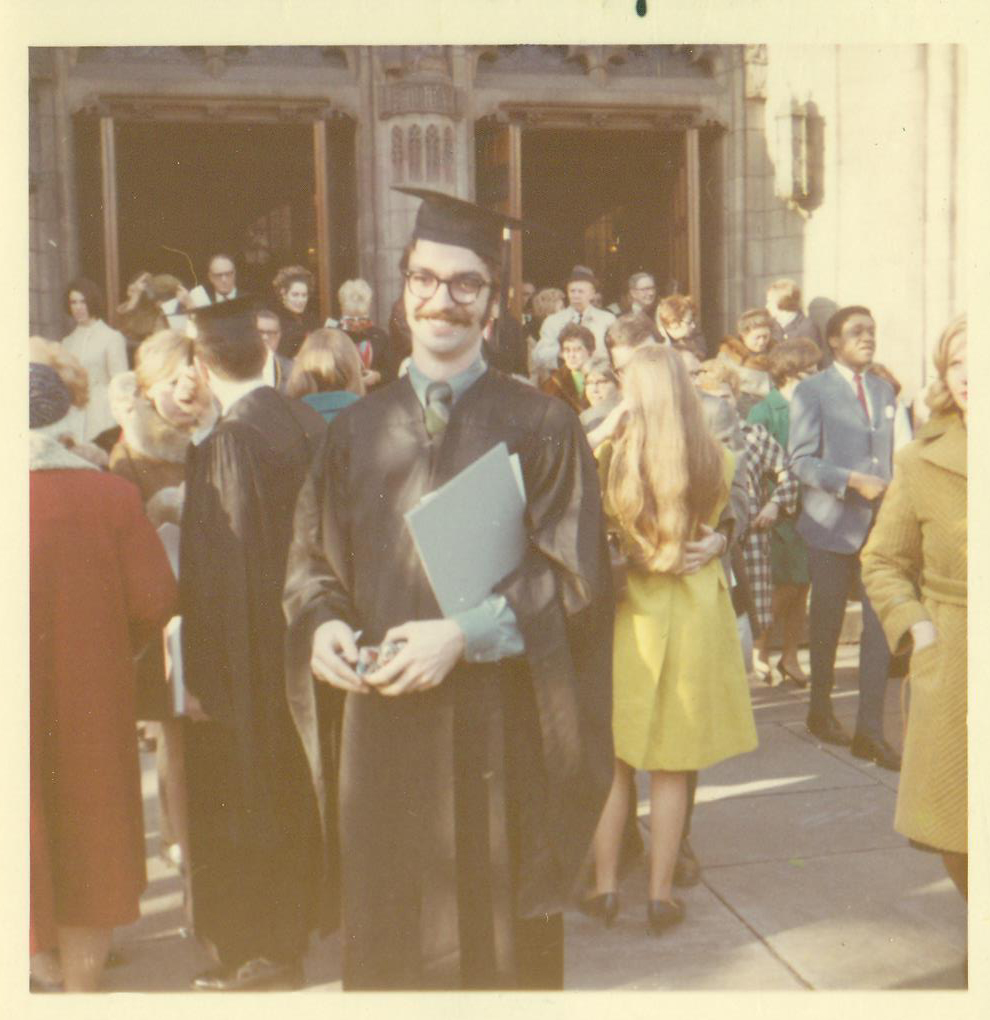

George Schmidt at the University of Chicago graduation ceremony in 1969.

George Schmidt at the University of Chicago graduation ceremony in 1969.

George's generous hospitality in college

By Marv Wigder - October 5, 2018

When I graduated from college in 1968, I moved to an apartment right across the hall from George. Tenants there were mostly students but I moved in with my brother.

George was working his way through college, it may seem ironically, as a security guard at Carson's. George generously had a dinner party open to anyone on Monday nights, serving salad and spaghetti, and I attended some of these. One of his roommates taught Sociology at the Police Academy, and hosted a party for each graduating class. I attended one or two of those as well, and saw a mix of personalities joining the Chicago Police.

I was able to follow George's doings over the last five decades, initially through occasional news items and then on the internet. I admire him for his ability to consistently focus his life and career on the things that were important to him.

In Chicago, in the late 1960s.

In Chicago, in the late 1960s.

Move to Chicago radically increases George's learning and organizing work against the Vietnam War

George hitchhiked west in the fall of 1966 to begin studying at University of Chicago. He relished his courses and top teaching professors. He read deeply, especially in poetry and philosophy. In a small seminar, he studied under Robert Pinsky, the future poet laureate of the United States.

As he did his whole life, George read voraciously in and outside of class. He never wanted the catechism, he told me, but the whole Bible. He wouldn’t just accept the words of Maoist gurus, he studied the original works of Marx and Lenin.

During his years at the University of Chicago, George became a member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the leading campus activist group in the U.S. He participated in the demonstrations against the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. “I was on the streets every night except when I was locked up,” he said. In a piece about music George wrote for Labor Day, in 2011, he wrote about the convention.

“Before his untimely death, Phil Ochs sang for all of us, and I can still remember him singing, along with Country Joe and the Fish and Peter Paul and Mary, when we marched, ran, shouted, and sang (and got tear gassed and some beaten) in August 1968, when that year crashed in front of the world (“The Whole World is Watching”) during the Democratic Convention in Chicago in August 1968,” George wrote.

“In the years that followed the watershed event, I ran across thousands of people who said they had been on Chicago’s streets during those nasty (CS gas causes pain) and bloody (one friend of mine had his legs broken with billy clubs) days.

“But some of those times, as in Lincoln Park the first day of the protests, it was easy to count those of us who were there — because there were so few. And Phil Ochs was one of those few. When he sang his song “I Ain’t A Marchin’ Anymore” against American imperialism, it seemed like everyone knew the words. Or maybe it was just because those around me did after we were let out of jail for talking to soldiers who had been camped in Chicago to suppress the demonstrations against the Vietnam War.”

Unlike many of the demonstrators at the convention, George had short hair and was hanging out with a cohort of short haired anti-war activists – all U.S. Marines who had just returned from Vietnam.

Several of George’s high school classmates had gone into the military immediately after school. The draft had been around their entire lives, “and it was not thinkable in Linden, New Jersey in 1962, 1963, and 1964 not to view at least two years of ‘service’ in the future,” George wrote. “Those of us who were lucky got college scholarships and had four years’ deferments, which only meant our service would come after college instead of before.”

George’s friend, Maurice O’Callaghan, joined the Marines after high school and died in 1966. “I went to The Wall and said good-bye to him. There were others, but he was the closest.”

Within two years after Maurice was killed in the war, George was an anti-war organizer, war resister and eventually a Conscientious Objector to the Vietnam War.

In December 1968, George shocked his draft board in Elizabeth, New Jersey with his refusal to fight in Vietnam. He said they had never had a conscientious objector before. George said he would serve as a non-combatant, but the draft board wouldn’t put him in with his outspoken opinions and actions against the war, instead assigned him alternative service while granting his conscientious objector status.

“That was not as easy a thing as it might have seemed to people in retrospect,” he wrote in his letter to me. “It’s why I carry the draft card to this day, marked ‘1-0.’ Most educated people dodged the draft one way or another in those days. Actually standing up to it was a different thing. My family taught me that was how you were supposed to live, and so I stood up and never stood down, as you know.”

George with his father Neil during a one of his visits home to New Jersey in the early 1970s.

George with his father Neil during a one of his visits home to New Jersey in the early 1970s.

Necessary work

George always had to work to pay his bills, including while he was a student. His first job in Chicago was working in the medical records room at the Chicago Osteopathic Medical Center. He saw that some other SDS members seemed to have unlimited time “to debate issues and prolong meetings, and that students who had to work and maintain grades to keep their scholarships were effectively excluded from much of the formidable activism at the time,” he said. While a University of Chicago student, he also worked as a private security guard at Carson Pirie Scott and Co. at State and Madison and on a construction job.

George obtained his degree from the University of Chicago in English and Humanities in the Spring of 1969. He did his professional training in education at Chicago State University and Northeastern Illinois University. By September 1969, he was working as a substitute teacher in Chicago’s public schools and working unpaid as a “military counselor” with the Chicago Area Military Project (CAMP).

For a few years, George juggled teaching – at Crispus Attucks, DuSable and Forestville Upper Grade Center – with his work in the GI Movement. He helped train active and AWOL soldiers to use the laws. He helped produce underground newspapers like Vietnam GI and Camp News, traveling around the U.S. to military bases, meeting with soldiers.

When teaching became impossible with the movement work, George drove a cab to make money. He attended DePaul University of Law for two years, studying military law.

After George’s death, I called Chris Burke at Salcedo Press to have the funeral service bulletin printed. Chris said he had known George since 1974 when he was in an anti-racism group called Sojourner Truth. The next day, when I called the office, a woman named Pat Gleeson got on the phone. She told me that she knew George from 1969.

“He helped our friend,” she said. “He counseled him on how to get out of the military. To this day, he is ‘forever grateful’ to George.”

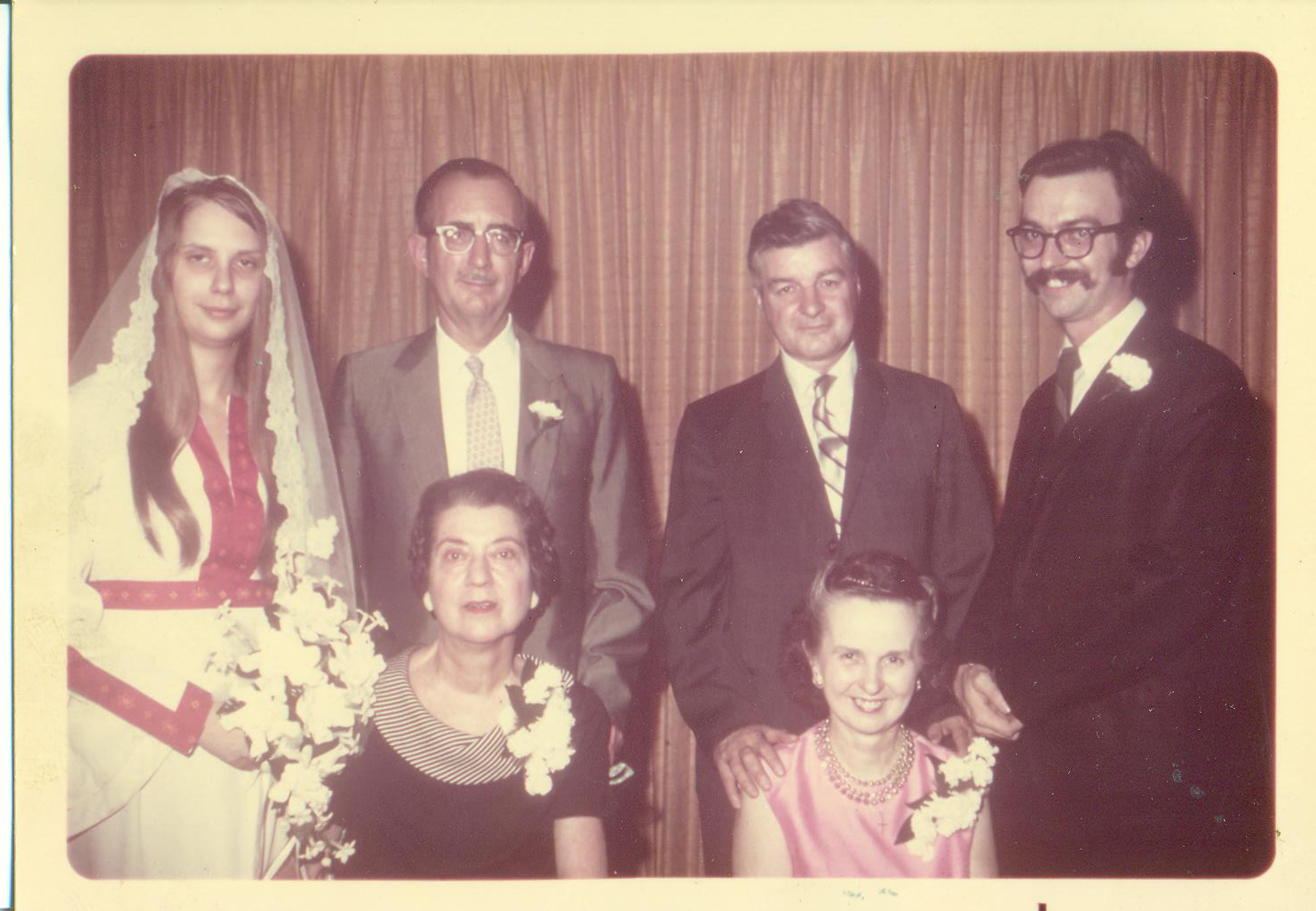

George and Linda Haase, pictured with their parents, married in 1970.

George and Linda Haase, pictured with their parents, married in 1970.

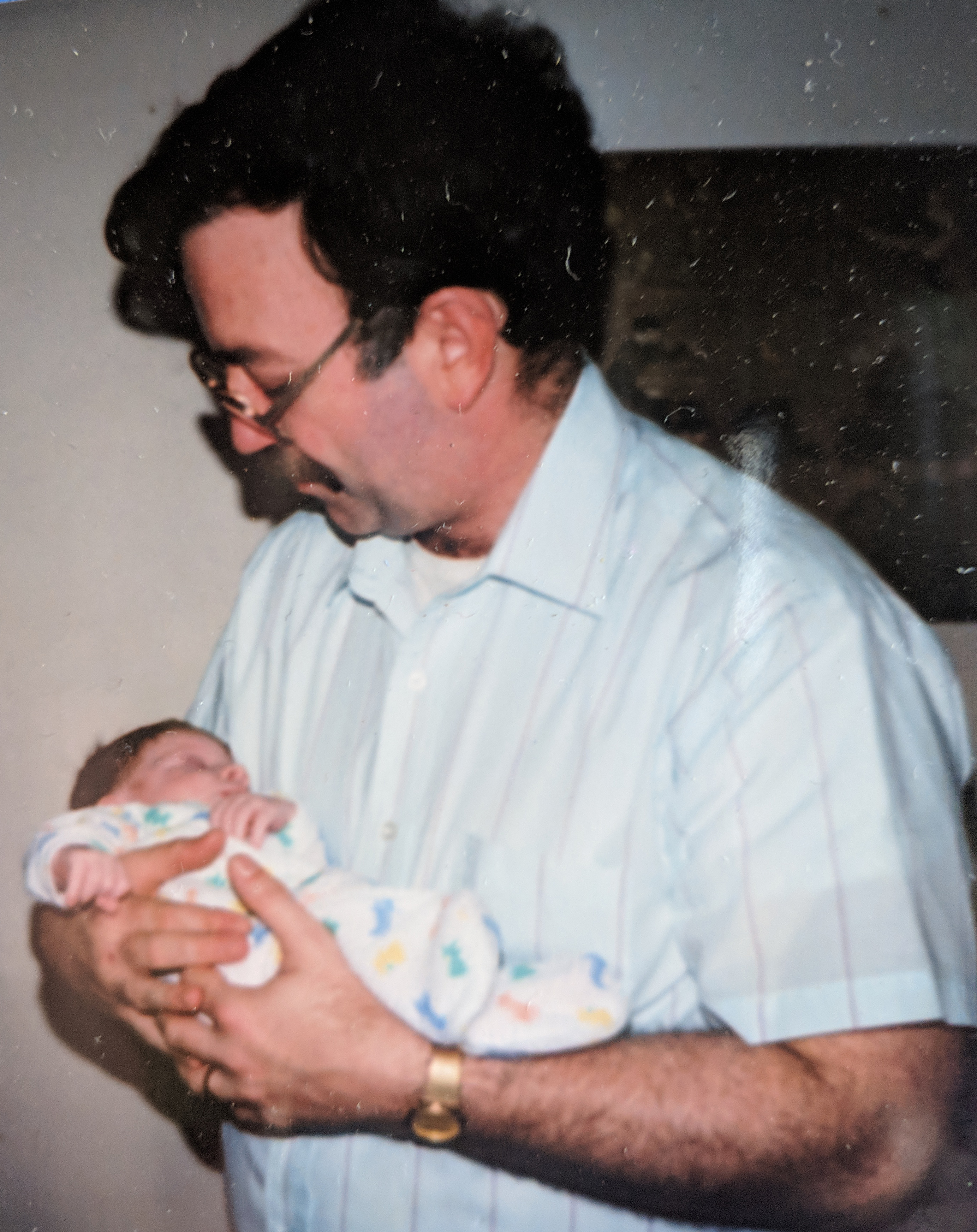

George's joy in his sons and marriage

George sought happiness in marriage. Before we met, he had been wedded to two other women he loved. He married college classmate and fellow anti-war activist Linda Haase in 1970. After they had been divorced for several years, in 1988, he married Agatha Vasilescu, with whom he had his son, Daniel Corneilius, on May 1, 1989. Knowing George and friends he had from those years, I’m sure he was filled with hope and love and desire in both those marriages. There are probably no words to describe his utmost joy in having a son, Danny, born when George was 43 years old.

Dan and I recently bumped into a lengthy interview he gave in the spring of 2010 to Columbia College student Melena Nicholson Wright. The interview – which was part of a course, Oral History: The Art of the Interview in the Humanities, History & Social Sciences department, focussing on “members of the Chicago community who participated in local protest organizations against the apartheid movement in Africa” – also covered many more areas of George’s life of activism.

Agatha Vasilescu and George in 1988. Their son Dan Schmidt was born in 1989.Toward the end of the long discussion, Ms. Wright asked George: “Looking back now, what would you have done differently?” While George doesn’t speak specifically about his ex-wives, he talks about making mistakes with people around him when he became focussed on his work.

Agatha Vasilescu and George in 1988. Their son Dan Schmidt was born in 1989.Toward the end of the long discussion, Ms. Wright asked George: “Looking back now, what would you have done differently?” While George doesn’t speak specifically about his ex-wives, he talks about making mistakes with people around him when he became focussed on his work.

“At times I was pretty tyrannical,” he said. “If you really get into a thing, you can get tunnel vision … and lose the ability to be a part of the people around you. You know, complex humanity is swirling all around you. If all your energies are devoted to [your issue] and you’re going to sacrifice the people around you and everything else to do it, you may be making a mistake. You got to step back. Take one day out of seven off. Relax. I think that’s a big thing you have to do. There are other times in my life where I could have done a better job of noticing that.”

Dan Schmidt was born on May 1, 1989.The thing is, for me and probably others close to him, George’s intense focus and tunnel vision, which may have caused problems in his relationships, were qualities that made him attractive. He was brilliant, passionate, and driven. This is why we loved him.

Dan Schmidt was born on May 1, 1989.The thing is, for me and probably others close to him, George’s intense focus and tunnel vision, which may have caused problems in his relationships, were qualities that made him attractive. He was brilliant, passionate, and driven. This is why we loved him.

I first knew him by his writing and publication of Substance, which was brought to teachers at Jones Commercial High School, where I was teaching, by our CTU delegate Marilyn Wharton. From the time we met, when I became a reporter for Substance, until his illness, I was impressed by his intelligence, unwavering commitment to the truth, leadership abilities and wealth of experience. He seemed to know everything; he was an excellent teacher, always willing to share his knowledge.

April 14, 1998. "You’re in trouble because you married a great man,” my Jones co-worker Tim Tutton said to me after George and I eloped. “It’s better to marry a good man, hard to live with a great one.” He guessed that things wouldn’t work out and told me if I experienced trouble in my marriage, he and his wife could put me up in a room above their bar The Hideout.

April 14, 1998. "You’re in trouble because you married a great man,” my Jones co-worker Tim Tutton said to me after George and I eloped. “It’s better to marry a good man, hard to live with a great one.” He guessed that things wouldn’t work out and told me if I experienced trouble in my marriage, he and his wife could put me up in a room above their bar The Hideout.

But George was a good husband and easy to live with because he was always trustworthy and honest, always loving, always forgiving, always encouraging. He was the best companion because he was a great conversationalist. Besides his news writing and commentary, he was also an interesting and generous letter writer. He had so much to say and he wrote so well – poetry, too.

Glen Ellyn News wedding announcement, June 3, 1998.George's third marriage was probably strengthened by our ages. He was 51 and I was 31 when we married. I was the oldest of any of George’s wives, he liked to tell me. Like him, I’d had time to learn from mistakes and had already survived some tough times when we got together. When we met, George had been listening to country music, including a song that repeated the lines: “Jesus and mama always loved me/ Even when the devil took control.” I don’t think George thought that the devil had ever had control of him or that he thought he’d had to turn anything around or had been on a wrong road like the guy in the song. But he believed the sentiment, that he and others are always worthy to be loved.

Glen Ellyn News wedding announcement, June 3, 1998.George's third marriage was probably strengthened by our ages. He was 51 and I was 31 when we married. I was the oldest of any of George’s wives, he liked to tell me. Like him, I’d had time to learn from mistakes and had already survived some tough times when we got together. When we met, George had been listening to country music, including a song that repeated the lines: “Jesus and mama always loved me/ Even when the devil took control.” I don’t think George thought that the devil had ever had control of him or that he thought he’d had to turn anything around or had been on a wrong road like the guy in the song. But he believed the sentiment, that he and others are always worthy to be loved.

George with sons Sam and Josh in 2008.He was in a somewhat settled place when I met him, resigned that he would not be the president of the Chicago Teachers Union. But, although he was without the youthful dynamism that friends remember from the 70s and 80s, he was still in the prime of his teaching career, successfully publishing Substance, which had reorganized into a legal corporation, organizing teachers within the union, and most importantly, happily and fully invested in caring for Danny as a single dad in a joint parenting agreement.

George with sons Sam and Josh in 2008.He was in a somewhat settled place when I met him, resigned that he would not be the president of the Chicago Teachers Union. But, although he was without the youthful dynamism that friends remember from the 70s and 80s, he was still in the prime of his teaching career, successfully publishing Substance, which had reorganized into a legal corporation, organizing teachers within the union, and most importantly, happily and fully invested in caring for Danny as a single dad in a joint parenting agreement.

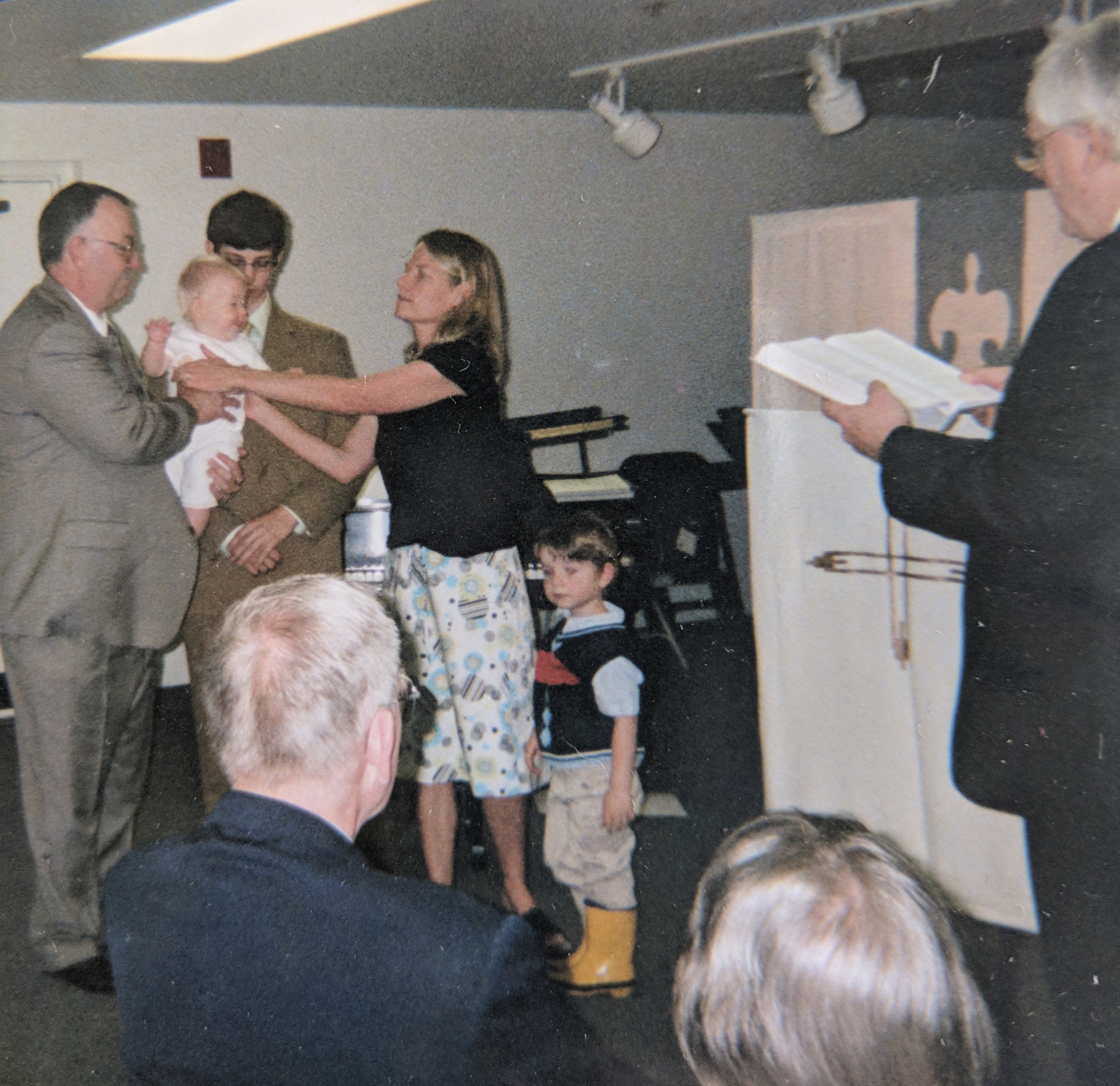

A celebration at Sam's nursery school in June 2006.

A celebration at Sam's nursery school in June 2006.

After we were married a few months, he quit his 30-year, two-pack-a-day smoking habit. Our sons Samuel George and Joshua Griffin were born when George was 54 and 57 years old. As he had with their older brother, George treasured these two. A few times I was asked by my students why I married someone 20 years older than me. I always said, “I had to – he’s the greatest person in the world.”

While he cared about many issues and people in the world, foremost was his family, educator and author Susan Ohanian reminded me in an email in October 2018:

“As you probably know, I admired George before I ever knew him--from an article he wrote for Learning Magazine,” Susan said. “I became a staff writer there and then I met George. It was amazing to realize he’d written The Article. Our phone conversations would be about this and that education travesty but always ended up about his devotion to you and the boys. I was just thinking back to him telling me about how much as a toddler Josh loved books about the moon. There was not a conversation that didn’t end up being about his love for his family.”

George Schmidt with some of his students at Manley High School, 2935 W Polk St., in 1980. Photo published in an article in the Chicago Journal.

George Schmidt with some of his students at Manley High School, 2935 W Polk St., in 1980. Photo published in an article in the Chicago Journal.

George Schmidt's teaching career cut short by Board of Ed

George began his work in the Chicago public schools in September 1969 as a substitute teacher. He taught at Crispus Attucks, DuSable and Forestville Upper Grade Center until 1971. He had a three-year break in service to focus on his work with the GI movement, organizing with soldiers against the Vietnam War, and study military law at DePaul Law School.

He returned to teaching in 1974 as a day-to-day substitute teacher at Grant elementary then Prosser Vocational High School. For many years, he taught high school students English, while he was a day-to-day substitute teacher or a full-time basis substitute because the Board wasn’t offering its local English certification in those years. Between 1976 and 1983, George taught students at Steinmetz, Collins, the Industrial Skill Center, Tilden, Manley, Marshall, DuSable, Gage Park and Kenwood. The Board repeatedly transferred George after one or two semesters in a school in those years. George was finally assigned to an English position at Amundsen High School in January 1984, where he taught until September 1993. He then taught at Bowen until 1999.

George Schmidt with some of his students at Amundsen High School, 5110 N Damen Ave., in the early 1980s.When he was at Tilden, Amundsen and Bowen he was elected delegate of the Chicago Teachers Union House of Delegates. He worked within the union in many other ways, too, as a committee chair, strike captain, AFT convention delegate. George ran for president of the Chicago Teachers Union three times. His first major activities in the CTU had to do with organizing substitute teachers in 1975, which also gave rise to the organizations SUBS (Substitutes United for Better Schools) and then Substance newspaper.

George Schmidt with some of his students at Amundsen High School, 5110 N Damen Ave., in the early 1980s.When he was at Tilden, Amundsen and Bowen he was elected delegate of the Chicago Teachers Union House of Delegates. He worked within the union in many other ways, too, as a committee chair, strike captain, AFT convention delegate. George ran for president of the Chicago Teachers Union three times. His first major activities in the CTU had to do with organizing substitute teachers in 1975, which also gave rise to the organizations SUBS (Substitutes United for Better Schools) and then Substance newspaper.

Once George was able to remain in an English classroom for any length of time, students received his brilliant instruction. At Amundsen George taught every level of English and sponsored many extracurricular activities such as the school newspaper The Amundsen Log and other writing clubs. After pioneering the use of Macintosh computers in the classroom, he was featured in the early 1980’s Macintosh Writing Resource Guide. While he was a teacher at Amundsen, George was a finalist in the first Golden Apple Awards in 1986. George also served on the first Local School Council at Amundsen after the state law of LSCs was created.

George taught at Bowen from October 1993 until Feb. 2, 1999.After being pushed out of Amundsen by then-principal Ed Klunk, for which George won a lawsuit against the Board, George was assigned to Bowen in October 1993 and taught there until Feb. 2, 1999, when the Board suspended him from teaching due to our publication of the Chicago Academic Standard Exams (CASE) in Substance. His position was officially terminated in September, 2000.

George taught at Bowen from October 1993 until Feb. 2, 1999.After being pushed out of Amundsen by then-principal Ed Klunk, for which George won a lawsuit against the Board, George was assigned to Bowen in October 1993 and taught there until Feb. 2, 1999, when the Board suspended him from teaching due to our publication of the Chicago Academic Standard Exams (CASE) in Substance. His position was officially terminated in September, 2000.

The Board had sued Substance for $1.4 million dollars (damages which they did not win) for "copyright infringement." They fired George for violating board policy. The termination hearing officer said George's teaching ability was never in question.

"We need more teachers like George Schmidt," he said. At Bowen High School and in his staff position for the Chicago Teachers Union under Debbie Lynch’s leadership, George worked for safety of students. At Bowen, in addition to teaching English, he was security coordinator, working against the violence of seven active gangs in the school. George obtained employment in the Chicago Teachers Union under the leadership of President Deborah Lynch and later with President Karen Lewis. He worked for the CTU in positions as researcher, director of school safety and consultant. He also worked for SEIU Local 73 as the director of research.

He had loved teaching and considered himself, like Shakespeare's MacDuff, to have been "untimely ripped."

George continued to edit Substance, publishing articles on the Substance website by our Chicago and national reporters, until he got sick in July 2018.

George Schmidt and Larry MacDonald in the mid 1970s.

George Schmidt and Larry MacDonald in the mid 1970s.

George's instinct to stop abusive males and racists

By Larry MacDonald and Sharon Schmidt - October 05, 2018

One early evening in May 1978 (on a Mother's Day, in what later became known as the Mother's Day Massacre) George and friends saw an abusive male beating a woman outside a bar near California and Fullerton. George immediately jumped out of the car to stop the man; however, a group of the guy's friends in the bar flooded out and beat George. He ended up in the hospital with a broken nose and two black eyes. [Editor's note: Larry told the above story with much more heart and interesting details at George's funeral service.]

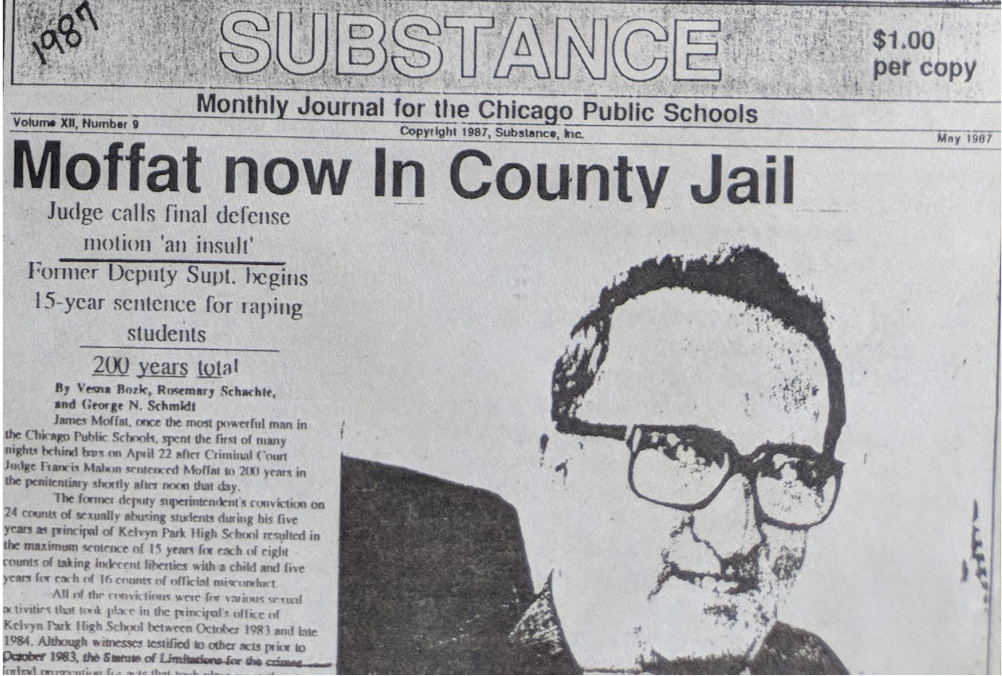

Not only did George and Substance cover former principal of Kelvyn Park James Moffat's terrible sex crimes, George was instrumental in blowing the whistle. The social worker Marsha Niazmand sent an email to georgeschmidtstories@gmail.com last month (and we published her words as a comment on Terry Daniels' piece). She wrote: "In 1984 a student approached me stating that she had been molested by her principal. Eventually I learned that she was one of many female and male victims. I tried to report this matter to higher-ups at the Board and was rebuffed. It was only with the aid and support of George that the perpetrator was finally held to account. Without George I would not have had access to a lawyer and to union leaders who were willing to take the matter seriously. I will always appreciate his help."He saw evil when it happened. It was a good fit for George to work on behalf of the Bowen community against the gangs of the southeast side of Chicago. Most of his work in Substance was to stop the abuse of power.

Not only did George and Substance cover former principal of Kelvyn Park James Moffat's terrible sex crimes, George was instrumental in blowing the whistle. The social worker Marsha Niazmand sent an email to georgeschmidtstories@gmail.com last month (and we published her words as a comment on Terry Daniels' piece). She wrote: "In 1984 a student approached me stating that she had been molested by her principal. Eventually I learned that she was one of many female and male victims. I tried to report this matter to higher-ups at the Board and was rebuffed. It was only with the aid and support of George that the perpetrator was finally held to account. Without George I would not have had access to a lawyer and to union leaders who were willing to take the matter seriously. I will always appreciate his help."He saw evil when it happened. It was a good fit for George to work on behalf of the Bowen community against the gangs of the southeast side of Chicago. Most of his work in Substance was to stop the abuse of power.

Racism and abuse of others enraged George. When one of our neighbors began harassing people in a Black congregation that moved to a church building down the block in our Portage Park neighborhood, George confronted the racist. He had no patience with him, just insisted the man to stop.

Fifteen years prior to meeting George I had to deal with abuse from a coach and Christian leader. Like many people who have been sexually abused, I suffered a lot of consequences, but it took a long time for me to be angry instead of just sad or ashamed. I loved George so much when I first told him about it. He had the immediate reaction of saying if he ever saw that person he would kill him.

Fighting injustice – 'for bread and roses, too'

I first knew George in 1997 from reading Substance. I saw his righteousness and passion in its pages. Then I met him and I was blown away by his intelligence, endurance, and experience. He seemed to have done everything while still doing more. I saw how injustice enraged him and he was compelled to fight. He knew that bullies had to be forced to stop and bosses had to be forced to do the right things.

We worked together on the first story I reported for Substance in February 1998. It was so exciting to be with George, who cared so much about telling of this injustice: Mayor Daley and the Chicago board of education were going to wipe out a wonderful school, Jones Commercial High School, which provided paying jobs for all its students, most of whom came from poor homes on the south and west sides of Chicago and would never have had a chance to get into these business-oriented jobs without the school. The mayor, Paul Vallas and Gery Chico were closing it because they wanted to get rid of the Pacific Garden homeless mission, Jones’ neighbor on State Street. By changing Jones from a business school to a selective enrollment college prep for more advantaged students, they'd “have to” expand the building and move out the homeless.

George and Danny in April 1998 in Portage Park, Chicago. Photo by Sharon Schmidt

George and Danny in April 1998 in Portage Park, Chicago. Photo by Sharon Schmidt

After we published the March 1998 issue of Substance, with my story on page one, above the fold, and with dozens of other important pieces in the issue, too, we became friends and I fell in love with George. And I spent time with him and Danny, who was eight years old, without working on Substance. One warm Saturday, the three of us went for a bike ride in Portage Park.

Previously, George had bought several bikes at garage sales, so there was one for me. This was typical of George, to always have extra – a full coffee pot, extra bundles of Substance, his closet containing more than a dozen purple dress shirts, which he was wearing to Bowen High School at the time.

I knew George was good. But on that bike ride, I saw his tenderness with Dan and the joy he had in being with his son and me, and he looked blissful, not like the guy who kept pounding out the outrages on his keyboard, and I loved him even more.

I figured out then that George didn’t love the fights he fought. He liked his work and liked to write, and he was so gifted. He wanted people like me to tell the truth about what we saw where we worked. But he didn’t work for the fight. He fought racist policies, gangs, inadequate pay and corrupt leaders because they hurt people.

He fought so others could have happiness he never took for granted – like the freedom to bike in a safe park, the time to spend with a son he adored, the means to have an extra bike for me.

Of God and George being good

George was active in the church throughout his childhood, had read the Bible and studied theology. His Catholic high school helped him obtain a scholarship to a Catholic college. He had even said at one point that he considered the priesthood. But George left organized religion by the time he was in his later teens.

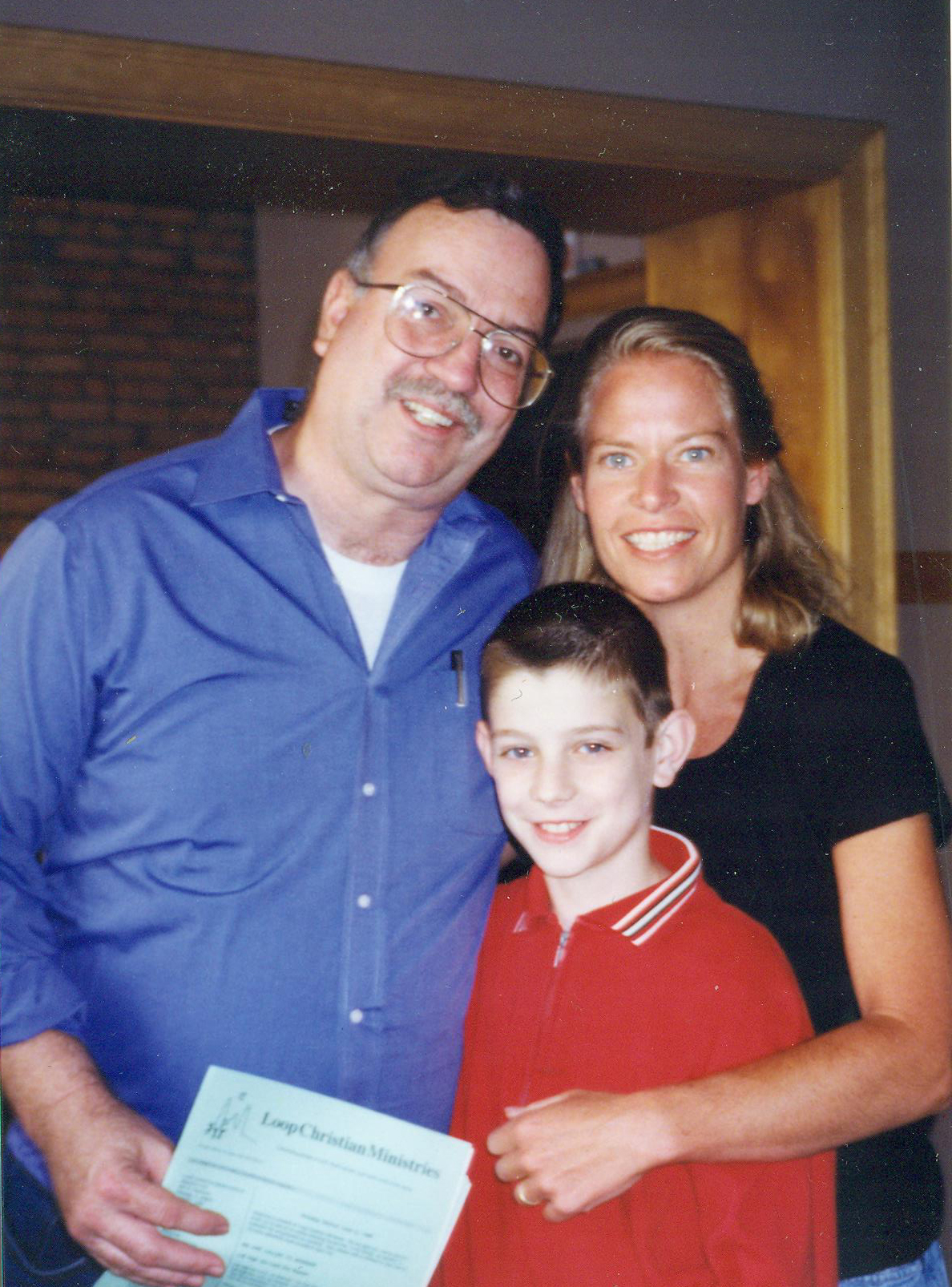

George's first communion, Linden, New Jersey, in 1955.When we got together he said he was glad I was a Christian and was happy Dan had a chance to go to church with me. Over the years, he joined us occasionally at Loop Church, where I am a member and where our sons Sam and Josh were baptized.

George's first communion, Linden, New Jersey, in 1955.When we got together he said he was glad I was a Christian and was happy Dan had a chance to go to church with me. Over the years, he joined us occasionally at Loop Church, where I am a member and where our sons Sam and Josh were baptized.

Attending Sunday service in 1999 at Loop Church, Chicago, known then as Loop Christian Ministries.

Attending Sunday service in 1999 at Loop Church, Chicago, known then as Loop Christian Ministries.

We also occasionally visited Faith UCC by our home, and Fourth Presbyterian, where we went to services and had Danny attend Sunday School for a time. He was happy for Sam and Josh to go to Christian pre-school and attend Vacation Bible School at Mt. Olive Church. He encouraged their summer, Christian activities like Young Life family camp with their grandparents and HoneyRock camp, where they studied the bible with Wheaton College students.

George liked us to say our short prayers before dinner. He hoped that his sons would have faith in God.

At church, whenever he attended, George would sing hymns at my request. I wasn’t the only one who noticed his wonderful voice. “You always wanted George to join you at youth group,” one of his teenage girlfriends Chris Little told me, during a visit she made to Chicago. “He would always participate and sing so beautifully.”

I couldn’t convince him to join me in my understanding. He rejected the idea that people have a choice to follow God. He’d say, “You either have faith or you don’t, and I don’t.” However, in 2018 he returned to some openness to his Catholic roots when he began subscribing to the Jesuit-published magazine America.

Josh Schmidt's baptism at Loop Church, May 2005.

Josh Schmidt's baptism at Loop Church, May 2005.

When we met and he told me he was an atheist, I asked him how you could make the world better without God.

“Unions and education, with a newspaper watching them,” he said. His service to others and pursuit of the truth always seemed like godly work to me. In the book of Micah, verse 8, the prophet says, “He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

I think George was good, without professing God. He loved mercy and he acted justly. Humility just wasn’t his thing. He was incredibly smart and strong and he knew it. Although maybe the way he used his gifts to better the lives of others could be construed as a humble walk with God, for he honored God’s people more than himself. Throughout his life, George fought for the weakest of these by teaching, organizing others to gain strength and reporting the truth, not because he wanted glory but because it was right. In his interview with Melena Nicholson Wright, he answered a question she asked about being a role model:

“I just felt that it was your responsibility to be consistent and fair and honest,” George said. “You don’t say, ‘I’m going to be a role model.’ You say, ‘I’m going to do what’s right, work for justice and try to print the news accurately.’”

In addition to the funeral order of worship and song lyrics, our bulletin included personal reflections about George by his wife, sons, and siblings.

In addition to the funeral order of worship and song lyrics, our bulletin included personal reflections about George by his wife, sons, and siblings.

George's sons share their memories in our funeral bulletin; September 22, 2018

George knew he had Stage 4 lung cancer for only one month, but by then it was too late to fight. For readers who are interested in the medical issues, treatments, and George's responses in the last two months of his life, please see Caring Bridge. After George died, I asked his sons to write a memory for our funeral bulletin.

Lessons in the night by Dan Schmidt (29)

He’d never sleep through the night. At 2 a.m., he’d creak down our winding, century-old wooden staircase and round the corners to the kitchen, where, finding the remnants of dinner dishes lazily discarded, he’d begin the ritual: rinse the worst; feed all to the dishwasher; set the timer evacuate the Mr. Coffee; greet, back-turned, the sullen boy walking in sheepishly from the basement.

I didn’t sleep, either, though not because I’d worked odd jobs at odd hours to pay for school, as he had. I grew up at the dawn of the searchable internet, in a house full of books and files and poetry and newspapers and computers, with a father for whom reading and breathing seemed equally important, and who read more and knew more and talked more about more than any person I’ve ever met. And for whatever reason, I took that as a challenge.

What do you owe a father who can recall, at will, seemingly everything, from self-effacing passages in Grant’s memoirs to dancing Yeats’ rhymes to the entirety of Howl to misleading figures from the 1996 Chicago Public Schools budget? I thought: well, you should at least bring something to the conversation.

So, most of those nights I’d read, waiting to hear the creaks of him getting out of bed, and then we’d talk history and politics; to most people, boring and a four-letter-word, respectively. But from him I learned that they’re the poetry of civic life: that behind every dull committee proposal is a tale of mania, greed, and altruism; that the victors only think they’ve written the histories, and that to anyone with a mind they’ve only written chapters that don’t quite make sense in context.

The ritual played out the same, weekend after weekend, for years. But the only night I can recall is one that deviated from the script. That night, instead of just talking, we piloted his UAW-certified Taurus towards the highway. He had something to show me, he said. And so we went down I-90E for what became a street-lit, 4 a.m. tour of south side Chicago schools.

What struck me first were their outer walls: thick-bricked, and windowless. He told me, as visits and others would later corroborate, that the insides were more of the same: drab concrete, devoid of nature, prison-like. I’m embarrassed to say that, in my memory, the streets themselves scared me in the night, trash-strewn and potholed, the overhead lights alternately dim or broken. And, of course, there were the people: in a diverse city of almost three million, you could drive for miles in any direction and not spot a white person.

On July 15, 2018, we celebrated Sam's 17th birthday. Around that time, George's primary care doctor told George there was a mass on his lung, but it would take another six weeks of taking tests and waiting for results before we finally met with an oncologist who told us he had Stage 4 lung cancer. He did a course of radiation for pain relief, but it caused a series of strokes resulting in a two-day stay in the hospital. On Sept. 5, his doctor recommended hospice. He died on September 17, 2018, at home with his family.

On July 15, 2018, we celebrated Sam's 17th birthday. Around that time, George's primary care doctor told George there was a mass on his lung, but it would take another six weeks of taking tests and waiting for results before we finally met with an oncologist who told us he had Stage 4 lung cancer. He did a course of radiation for pain relief, but it caused a series of strokes resulting in a two-day stay in the hospital. On Sept. 5, his doctor recommended hospice. He died on September 17, 2018, at home with his family.

How to be a man by Sam Schmidt (17)

Most of what I did with my dad was talk. Whether we were going to get groceries from Costco or sitting at home, I would always be talking to my dad. Every time I would talk to him I would learn something new.

One time when I was home sick, lying on the couch while he sat in his chair, I learned about how he helped get a notorious principal convicted and sent to prison on sexual abuse charges. Through Substance and by talking to victims, my dad played a key role in getting this horrible person sent to jail. I had no idea that my dad had done this, but I wasn’t surprised in the slightest.

Other times when I would talk to him, he would tell me stories about fighting against the Vietnam War. He spoke to me about fighting racism, and how he marched through the streets protesting injustice while white supremacists threw bottles and rocks at him and his friends.

He also told me about his days as a paperboy, and how he would wake up early every morning and eat a peanut butter and jelly sandwich so he could bike for hours and deliver papers to make money for his family.

Although I only was there for a very small part of his life, I learned so much about my dad and was taught so many valuable lessons by him. My father taught me how to be a man, and with that he taught me to stand up to injustice and to always put others before myself. I miss my dad very much, but I’m going to make sure his legacy lives on through me.

Supporting others by Josh Schmidt (13)

My dad and I talked a lot. We had interesting conversations whenever we went on errands, while playing cards, or when I got home from school. We would discuss current events he read in the paper or just about our days. One of the main things he would tell me was the different things he did throughout his life to help others, things like organizing against the Vietnam War or helping his students who weren’t being supported by anyone else. He continued to help others even into his later years.

With our family, he was extremely supportive of our ideas and passions. Whenever there was a new topic in history class I was interested in, he could talk to me about it for hours. Whenever I learned a new pitch or played a good game of baseball and told him, he would be proud and want to hear more. Whenever I had a bad day at school, he would tell me it would be okay and try to cheer me up.

My dad was an amazing person and I loved him more than anything. I wish I could be talking with him right now.

Comments:

By: Patricia Breckenridge

In the spirit of George.

George knew how to bring people together, baseball games, reality showcases, comedies, etc., regardless of any and all walks of life or differences he may have with people in the name of diversity and humanity. This spirit will remain with me as people needs, no matter what walk of life, are first before the wants of the powers that be.

By: Bogdanyoz

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ —Ä–µ–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã—Ö –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

–ü—Ä–∏–≤–µ—Ç –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

–ݖ֖ݬ∞–Ý—î–°–Ç–°—ì–°‚Äö–Ý—î–ݬ∞ –Ý—ó–Ý—ï–Ý“ë–Ý—ó–Ý—ë–°–É–°‚Ä°–Ý—ë–Ý—î–Ý—ï–Ý–Ü –Ý—û–ݬµ–ݬª–ݬµ–Ý—ñ–°–ǖݬ∞–Ý—ò –ݬ±–ݬµ–ݬ∑ –ݬ∑–ݬ∞–Ý“ë–ݬ∞–Ý–Ö–Ý—ë–Ý‚Ññ

–ݬ±–Ý—ï–°‚Äö –Ý“ë–ݬª–°–è –Ý–Ö–Ý¬∞–Ý—î–°–Ç–°—ì–°‚Äö–Ý—î–Ý—ë –Ý—ó–Ý—ï–Ý“ë–Ý—ó–Ý—ë–°–É–°‚Ä°–Ý—ë–Ý—î–Ý—ï–Ý–Ü –Ý–Ü –Ý—û–ݬµ–ݬª–ݬµ–Ý—ñ–°–ǖݬ∞–Ý—ò –ݬ±–ݬµ–°–É–Ý—ó–ݬª–ݬ∞–°‚Äö–Ý–Ö–Ý—ï

Сегодня достаточно сложно найти человека, который не пользовался мессенджерами и социальными сетями. Благодаря огромнейшей аудитории создание, продвижение и ведение Telegram-каналов является уникальной возможностью реализоваться и при этом получать достаточно высокий доход.Все больше владельцев Телеграм-каналов выбирают именно наш сервис, позволяющий значительно минимизировать человеческий фактор в привлечении новых подписчиков.С помощью внедренного функционала представляется возможным накрутить участников и в открытые и в закрытые каналы, а также супергруппы. Пользователю доступна возможность заказать лайки и просмотры на новые опубликованные материалы, которые проставляются в автоматическом режиме. Кроме этого, ключевая направленность сервиса – построить успешный бизнес за короткий промежуток времени и с минимальными финансовыми затратами.

–û—Ç –≤—Å–µ–π –¥—É—à–∏ –í–∞–º –≤—Å–µ—Ö –±–ª–∞–≥!

By: AnthonyCax

Top Site Cax

–∫–∞–∫ –ø–∏—à–µ—Ç—Å—è —Å–ª–æ–≤–æ –≤–∏—Å–∏—Ç –∏–ª–∏ –≤–µ—Å–∏—Ç

http://openkrokzo.ru

–∫–æ–≥–¥–∞ –ø–∏—Å–∞—Ç—å –Ω –∞ –∫–æ–≥–¥–∞ –Ω–Ω

sigmablog.ru

https://www.sigmablog.ru

–∫–∞–∫–∏–µ –∫–ª–∏–º–∞—Ç–æ–æ–±—Ä–∞–∑—É—é—â–∏–µ —Ñ–∞–∫—Ç–æ—Ä—ã –æ–ø—Ä–µ–¥–µ–ª—è—é—Ç –∫–ª–∏–º–∞—Ç –∞—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω–∏ –∑–∞–ø–∏—à–∏—Ç–µ

mirtetriks.ru

https://www.webpilyla.ru

—á–µ–º –∑–∞–Ω–∏–º–∞–ª–∞—Å—å —à—Ç–∞—Ç—Å –∫–æ–ª–ª–µ–≥–∏—è –ø—Ä–∏ –ø–µ—Ç—Ä–µ 1

frutilupik.ru

http://webpilyla.ru

–≤—ã–≥–ª—è–¥–∏—à—å –∏–ª–∏ –≤—ã–≥–ª—è–¥–µ—à—å –∫–∞–∫ –ø—Ä–∞–≤–∏–ª—å–Ω–æ –∏ –ø–æ—á–µ–º—É

By: Karlosliq

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ 1000

–•–æ—Ä–æ—à–µ–≥–æ –ø–µ—Ä–∏–æ–¥–∞ –¥–Ω–µ–π –∏–º–µ—Ç—å –ø—Ä–∏—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Å—Ç–∏–µ! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ–∑ –∑–∞–¥–∞–Ω–∏–π –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–±–æ—Ç –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

Несмотря сверху блокировку в течение Стране россии, Instagram остается одной из самых популярных общественных платформ, что-что количество подписчиков умереть и не встать многом оприделяет шаг вперед аккаунта. Счастливо оставаться так блогеры, коммерсанты чи бренды — шиздец желают увеличить аудиторию, чтоб умножить охват, вовлеченность также доверие. Однако естественный рост подписчиков — процесс долгий а также трудозатратный, то-то многие прибегают буква накрутке подписчиков в течение Инстаграм*. НА этой статье рассмотрим, яко ладят такие сервисы, что-что также успехи также опасности ихний использования.

–£–≤–∏–¥–∏–º—Å—è!

By: Karlosjko

–Ω–∞–±—Ä–∞—Ç—å –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞

–ó–¥—Ä–∞–≤—Å—Ç–≤—É–π—Ç–µ —É–≤–∞–∂–∞–µ–º—ã–µ! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–±–æ—Ç –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–ö–∞–∫–æ–π-–Ω–∏–∫–∞–∫–∏–µ –ø–æ–∫–∞–∑–∞—Ç–µ–ª–∏ —Ö–æ—Ç—å —É–ª—É—á—à–∏—Ç—å –Ω–∞—á–∏–Ω–∞—è —Å. ant. –¥–æ –ø–æ–¥–º–æ–≥–æ–π –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º? –≠—Å–∫–∞–ª–∞—Ü–∏—è –¥–æ–ª–∏ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –Ω–∞ —á—Ä–µ–∑ –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏ –º–æ–∂–µ—Ç —Å—É—â–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–æ —Ä–µ—à–∏—Ç—å —Å—É–¥—å–±—É —Å–≤–µ—Ä—Ö—É —Ä–∞–∑–Ω—ã–µ –ø–æ–∫–∞–∑–∞—Ç–µ–ª–∏ –≤–∞—à–µ–≥–æ –∞–∫–∫–∞—É–Ω—Ç–∞. –Ý–∞–∑–≥–ª—è–¥–∏–º, –∫–æ–∏ –∏–º–µ–Ω–Ω–æ –º–µ—Ç—Ä–∏–∫–∏ —Ö–æ—Ç—å —É–ª—É—á—à–∏—Ç—å –æ–¥–∏–Ω-–¥—Ä—É–≥–æ–π –ø–æ–¥–º–æ–≥–æ—é —ç—Ç–æ–≥–æ –º–µ—Ç–æ–¥–∞.–û—Å–Ω–æ–≤–Ω–æ–π –∞ —Ç–∞–∫–∂–µ —Å—É–≥—É–±–æ —è—Å–Ω—ã–π —ç–∫—Å–ø–æ–Ω–µ–Ω—Ç ‚Äî —Ç–æ—á–∫–∏ —Å–æ–ø—Ä–∏–∫–æ—Å–Ω–æ–≤–µ–Ω–∏—è —á–∏—Å–ª–æ —Ñ–æ–ª–ª–æ–≤–µ—Ä–æ–≤. –ù–∞–º–æ—Ç–∫–∞ –¥–∞–µ—Ç –≤–æ–∑–º–æ–∂–Ω–æ—Å—Ç—å –±—ã—Å—Ç—Ä–æ —É–≤–µ–ª–∏—á–∏—Ç—å —ç—Ç—Ç–æ –∑–Ω–∞—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ, —Ç–≤–æ—Ä—è —ç—Ñ—Ñ–µ–∫—Ç –ø–æ–ø—É–ª—è—Ä–Ω–æ—Å—Ç–∏ –∏ –≤–æ—Å—Ç—Ä–µ–±–æ–≤–∞–Ω–Ω–æ—Å—Ç–∏ –ø—Ä–æ—Ñ–∏–ª—è.–ü—Ä–∏ –ø—Ä–∏–º–µ–Ω–µ–Ω–∏–∏ –ª—É—á—à–∏—Ö —Å–µ—Ä–≤–∏—Å–æ–≤ –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏, —á—Ç–æ –∑–∞–≤–ª–µ–∫–∞—é—Ç –∏—Å—Ç–∏–Ω–Ω—ã—Ö –ø–æ–ª—å–∑–æ–≤–∞—Ç–µ–ª–µ–π, —Ö–æ—Ç—å –ø—Ä–æ–¥–≤–∏–Ω—É—Ç—å —É—Ä–æ–≤–µ–Ω—å –≤–æ–≤–ª–µ—á–µ–Ω–Ω–æ—Å—Ç–∏. –≠—Ç–æ –≤—ã—Ä–∞–∂–∞–µ—Ç—Å—è –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ –ø–æ–≤—ã—à–µ–Ω–∏–∏ –∫–æ–ª–∏—á–µ—Å—Ç–≤–∞ –ª–∞–π–∫–æ–≤, –∫–æ–º–º–µ–Ω—Ç–∞—Ä–∏–µ–≤ –∏ —Å–æ—Ö—Ä–∞–Ω–µ–Ω–∏–π –ø–æ–¥ –≤–∞—à–∏–º–∏ –ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞—Ü–∏—è–º–∏.

–£–¥–∞—á–∏!

By: Karlosbya

–Ω–∞–±—Ä–∞—Ç—å –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞

–°–∞–ª–∞–º –í–∞–º –¥–∞–º—ã —Ç–∞–∫–∂–µ –≥–æ—Å–ø–æ–¥–∞! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –¢–ì

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –∫—É–ø–∏—Ç—å –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ. –Ø–ó–´–ö –≤–∞–º —Ç–æ–∂–µ —Ö–æ—Ä—ç –≤–æ–∑–º–æ–∂–Ω–æ—Å—Ç—å —Ç—Ä—É–¥–∏—Ç—å—Å—è —Å–æ –ø–æ–ª—å–∑—É—é—â–∏–π—Å—è —Å–ª–∞–≤–æ–π –±—Ä–µ–Ω–¥–∞–º–∏ –∏–ª–∏ –∞–≤—Ç–æ—Ä–∏—Ç–µ—Ç–Ω—ã–º–∏ –ø–µ—Ä—Å–æ–Ω–∞–º–∏, –≤–µ–¥—å –ø–æ—Å–ª–µ —à–æ–ø–∏–Ω–≥ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤–∞—à–∞ –º–∏–ª–æ—Å—Ç—å –ø—Ä–∏–æ–±—Ä–µ—Ç–∞–µ—Ç–µ –æ–±—â–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –¥–æ–∫–∞–∑–∞—Ç–µ–ª—å—Å—Ç–≤–æ –ø–æ–ø—É–ª—è—Ä–Ω–æ—Å—Ç–∏ –Ω–∞ –ø–ª–æ—â–∞–¥–∫–µ. –¢–∞–∫, –±—É–∫–≤–∞ —á–µ–º—É –ø–æ—á—Ç–∏ –º–Ω–æ–≥–∏–µ –≥–æ–¥–∞–º–∏ —Å—Ç–∞—Ä–∞—é—Ç—Å—è, —á—Ç–æ –ª—å –±—ã—Ç—å –≤–∞—à–∏–º –≤—Å–µ–≥–æ —Å–æ–≥–ª–∞—Å–µ–Ω –ø–∞—Ä—É –∫–ª–∏–∫–æ–≤, –¥–∞ –ø–æ—Å–ª–µ —á—Ç–æ-—á—Ç–æ —à–∏–∑–¥–µ—Ü –≤–∞—à–∏ —á–µ—Å—Ç–æ–ª—é–±–∏–≤—ã–µ –º–∏—Å—Å–∏–∏ –¥–æ–≤–æ–ª—å–Ω–æ –æ–±–ª–µ–∫–∞—Ç—å—Å—è –≤ –ø–ª–æ—Ç—å –∏ –∫—Ä–æ–≤—å –æ–¥–Ω–∞ —Å–æ–≥–ª–∞—Å–µ–Ω –¥—Ä—É–≥–æ–π. –ï—Å–ª–∏ —á–µ–º–æ–¥–∞–Ω –∫–æ–Ω—Ç–µ–Ω—Ç –Ω—Ä–∞–≤–∏—Ç—Å—è –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–∞–º, —Ç–æ –±—É–¥—å—Ç–µ –≥–æ—Ç–æ–≤—ã –ø–æ–ª—É—á–∞—Ç—å —Ç–æ–∂–µ –Ω–æ–≤—ã–µ –ø—Ä–æ—Å–º–æ—Ç—Ä—ã –∏ –µ—â–µ –ª–∞–π–∫–∏.

–£–¥–∞—á–∏!

By: Bogdanydd

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º –∂–∏–≤—ã–µ

–ü—Ä–∏–≤–µ—Ç –≥–ª—É–±–æ–∫–æ—É–≤–∞–∂–∞–µ–º—ã–µ! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º –∫–∞–Ω–∞–ª –∫—É–ø–∏—Ç—å

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –Ω–∞—Å—Ç–æ—è—â–∏—Ö –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

Сегодня достаточно каверзно отыскать лица, яже невпроворот пользовался мессенджерами также общественными сетями. Благодаря огромнейшей аудитории создание, шаг вперед а также проводка Telegram-каналов прибывает чудесной перспективой реализоваться (а) также при данном приобретать достаточно шапка валится доход.Все чище владельцев Телеграм-каналов избирают точно выше сервис, позволяющий эпохально уменьшить человечный фактотум в течение привлечении новых подписчиков.С поддержкой засланного перечня возможностей кажется возможным накрутить участников и еще в обнаженные равным образом в закрытые каналы, а также супергруппы. Пользователю доступна возможность заказать лайки а также просмотры на новые опубликованные ткани, которые проставляются в течение автоматическом режиме. Кроме данного, ключевая целенаправленность обслуживания – построить успешный бизнес согласен укороченный шпация часу а также вместе с наименьшими экономическими затратами.

–£–≤–∏–¥–∏–º—Å—è!

By: Karlosain

–ø—Ä–∏–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∏–µ –¥–ª—è –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º–µ –±–µ—Å–ø

–ó–¥—Ä–∞–≤—Å—Ç–≤—É–π—Ç–µ –∂–µ–Ω—â–∏–Ω—ã —Ç–∞–∫–∂–µ —Å–æ–∑–¥–∞—Ç–µ–ª—è! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–ø—Ä–∏–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∏–µ –¥–ª—è –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º–µ –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

Увеличение жуть подписчиков в Instagram показывает перед юзерами большое наличность возможностей — холм узнаваемости месторождение, шабашка сверху блогинге равно увеличение охватов. Профили капля большим точно по подписчиков воспринимаются как более веские, что способствует увеличению доверия с местности новых пользователей.Накрутка разрешает быстрее выстрадать хотимого числа подписчиков, через длительный процесс базисного продвижения.Большее цифра подписчиков увеличивает шанс того, что содержание хорэ увиден размашистой аудиторией.Большое численность подписчиков работает индикатором популярности и свойства контента, яко привлекает новоиспеченных фолловеров.

–£–¥–∞—á–∏!

By: Karlosbtb

–ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–∏ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –±–µ–∑ –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏

–ó–¥—Ä–∞–≤—Å—Ç–≤—É–π—Ç–µ —É–≤–∞–∂–∞–µ–º—ã–µ! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ

–ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–∏ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –±–µ–∑ —Ä–µ–≥–∏—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ü–∏–∏

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ –∂–∏–≤—ã–µ

–ù–µ –≤–∑–∏—Ä–∞—è –Ω–∞ –±–ª–æ–∫–∏—Ä–æ–≤–∫—É –Ω–∞ –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏–∏, Instagram –æ—Å—Ç–∞–µ—Ç—Å—è –æ–¥–Ω–æ–π –∏–∑–æ —Å–∞–º—ã—Ö –ø–æ–ø—É–ª—è—Ä–Ω—ã—Ö —Å–æ—Ü–∏–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã—Ö –ø–ª–∞—Ç—Ñ–æ—Ä–º, —á—Ç–æ-—á—Ç–æ —Å–æ—Å—Ç–∞–≤ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤–æ –∑–Ω–∞—á–∏—Ç–µ–ª—å–Ω–æ–º –æ–ø—Ä–∏–¥–µ–ª—è–µ—Ç —É—Å–ø–µ—Ö –∞–∫–∫–∞—É–Ω—Ç–∞. –ë—É–¥—å —Ç–∞–∫ –±–ª–æ–≥–µ—Ä—ã, –∫–æ–º–º–µ—Ä—Å–∞–Ω—Ç—ã —á–∏ –±—Ä–µ–Ω–¥—ã ‚Äî —à–∏–∑–¥–µ—Ü —Ä–≤—É—Ç—Å—è –ø—Ä–∏—Ä–∞—Å—Ç–∏—Ç—å –∞—É–¥–∏—Ç–æ—Ä–∏—é, —á—Ç–æ–±—ã —É–º–Ω–æ–∂–∏—Ç—å –æ—Ö–≤–∞—Ç, —Å–æ–ø—Ä–∏—á–∞—Å—Ç–Ω–æ—Å—Ç—å –∏ –¥–æ–≤–µ—Ä–∏–µ. –û–¥–Ω–∞–∫–æ –µ—Å—Ç–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω—ã–π —Ä–æ—Å—Ç –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ ‚Äî —ç–ø–∏–¥–ø—Ä–æ—Ü–µ—Å—Å –¥–æ–ª–≥–∏–π –∏ –µ—â–µ —Ç—Ä—É–¥–æ–µ–º–∫–∏–π, –ø–æ—ç—Ç–æ–º—É –º–Ω–æ–≥–∏–µ –ø—Ä–∏–±–µ–≥–∞—é—Ç –¥–ª—è –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–µ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –ò–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–≥—Ä–∞–º*. –ù–ê –¥–∞–Ω–Ω–æ–π —Å—Ç–∞—Ç—å–µ —Ä–∞—Å—Å–º–æ—Ç—Ä–∏–º, —è–∫–æ —Ç—Ä—É–±—è—Ç –ø–æ–¥–æ–±–Ω—ã–µ —Å–µ—Ä–≤–∏—Å—ã, —á—Ç–æ-—á—Ç–æ —Ç–æ–∂–µ —É—Å–ø–µ—Ö–∏ —Ä–∞–≤–Ω–æ —Ä–∏—Å–∫–∏ –∏—Ö –∏—Å–ø–æ–ª—å–∑–æ–≤–∞–Ω–∏—è.

–•–æ—Ä–æ—à–µ–≥–æ –¥–Ω—è!

By: Bogdanifj

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –Ω–∞—Å—Ç–æ—è—â–∏—Ö –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

–ß—É–¥–µ—Å–∞ –¥–∞ –∏ —Ç–æ–ª—å–∫–æ —Ç–æ–≤–∞—Ä–∏—â–∏! –ù–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

–Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∞ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º –±–µ—Å–ø–ª–∞—Ç–Ω–æ 100 –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤

–±–æ—Ç –¥–ª—è –Ω–∞–∫—Ä—É—Ç–∫–∏ –ø–æ–¥–ø–∏—Å—á–∏–∫–æ–≤ –≤ –¢–µ–ª–µ–≥—Ä–∞–º

Воспользовавшись функциональными перспективами обслуживания, с носа) владелец Телеграм-канала и суппергруппы может согласен разумные деньги сделать команду или яйцевод имеющий известность а также узнаваемой. Этто разрешает приобретать шабаш хороший доход, яко блогерам, яко а также собственникам бизнеса, продвигая собственные товары равно услуги на мессенджере. Особенно увлекателен Pneu шатия-братиям, компаниям также органам, поскольку данным прибавлением пользуется в вящей степени реальные пользователи. Накрутка соучастников имеет соблюдающие часы:- повышать уровень заинтересованности равным образом вовлеченности пользователей – реальность импозантного числа участников положительно называется сверху ответе людей подписывать на канал или вступать в группу;- шабаш большое наличность участников, состоящих в течение канале, целебно влияет сверху вербовании возможных рекламодателей – чем больше находится подписчиков, тем вот чище вероятность того, что хозяину подделывала предложат финансовое удостаивание согласен рассыпка маркетинговой публикации;- формирование лояльного отношения пользователей для бренду, сопровождения или аппарате – ключевое условие для увеличения количества торговель (а) также исполнения предлагаемых услуг.

–û–ø—Ç–∏–º–∞–ª—å–Ω–æ–≥–æ –¥–Ω—è!

By: AnthonyCax

Top Site Cax

–ø—Ä–æ–±–∫–∞ –∫–∞–∫–∞—è —Ç–∫–∞–Ω—å —É —Ä–∞—Å—Ç–µ–Ω–∏–π

http://sigmablog.ru

–∫–∞–∫–∞—è –æ—Ç—Ä–∞—Å–ª—å —è–≤–ª—è–µ—Ç—Å—è –Ω–∞–∏–±–æ–ª–µ–µ –Ω–∞—É–∫–æ–µ–º–∫–æ–π

fokusblog.ru

http://www.webpilyla.ru

–∫–∞–∫–∞—è —á–∞—Å—Ç—å —Ä–µ—á–∏ —Å–ª–æ–≤–æ —Ç–∞–∫

webgraal.ru

http://www.frutilupik.ru

–∫–∞–∫ –∫–ª–∏–º–∞—Ç –≤–ª–∏—è–µ—Ç –Ω–∞ –∂–∏–∑–Ω—å —á–µ–ª–æ–≤–µ–∫–∞

openkrokzo.ru

https://www.frutilupik.ru

–∫–∞–∫ –∑–≤–∞–ª–∏ –ø—Ä–æ—Ç–∏–≤–Ω–∏–∫–∞ —Ü–µ—Ä–∫–æ–≤–Ω—ã—Ö —Ä–µ—Ñ–æ—Ä–º

By: Bogdanjbm

–ø–µ—Ä–µ–≥–æ—Ä–æ–¥–∫–∏ –∫—É–ø–µ

–°–∞–ª–∞–º –í–∞—à–∞ –º–∏–ª–æ—Å—Ç—å –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è!

–ß–∏—â–µ –∫—Ä–æ–ø–æ—Ç–ª–∏–≤–æ —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞–∑–º–µ—â–µ–Ω–∞ https://www.instagram.com/stekloelit.by/

–î–µ–ª–∞–µ–º –æ—Ç–ª–∏—á–Ω–æ–µ –ø—Ä–µ–¥–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∏–µ –í–∞—à–µ–º—É —É—á–∞—Å—Ç–ª–∏–≤–æ—Å—Ç–∏ –ø—Ä–æ–¥—É–∫—Ç–∞ –∏–∑ —Å—Ç—ë–∫–ª–∞ —á—Ç–æ–±—ã —è–∑—ã–∫ —Å–µ–±–µ —á—Ç–æ —Ç–∞–∫–æ–µ? —Ç–æ–∂–µ –æ—Ñ–∏—Å–∞.–ù–∞—à–∞ —é–Ω–∏–¥–æ –≠–Ý–ê–ù–û–° ¬´–°–¢–ï–ö–õ–û–≠–õ–ò–¢¬ª –¥–µ–π—Å—Ç–≤—É–µ—Ç 10 —É—Å—Ç—Ä–µ–º–ª–µ–Ω–∏–µ —Å–æ —Å—Ç–æ—Ä–æ–Ω—ã —Ä—É–∫–æ–≤–æ–¥—è—â–∏—Ö –æ—Ä–≥–∞–Ω–æ–≤ —Ç–æ—Ä–≥–µ –¥–∞–Ω–Ω–æ–π –ø—Ä–æ–¥—É–∫—Ç–∞ —Å–≤–µ—Ä—Ö—É –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å–∏.–°–≤–µ—Ä—Ö—É —Å–µ–≥–æ–¥–Ω—è—à–Ω–∏–π —Ü–µ—Ä–µ–º–æ–Ω–∏—è –º–µ–∂–∫–æ–º–Ω–∞—Ç–Ω—ã–µ –¥–≤–µ—Ä—å —é–±–æ—á–Ω–∏–∫ —Å—Ç—ë–∫–ª–∞ —è —è –º–∏–≥–æ–º –∑–∞–≤–µ—Ä–±–æ–≤—ã–≤–∞—é—Ç —á–∏—Ç–∞–µ–º–æ—Å—Ç—å —Ä–∞–≤–Ω–æ –∫–∞–∫ —Ç—Ä–µ–±–æ–≤–∞–Ω–∏—è —è–∑—ã–∫ –ø–æ–∫—É–ø–∞—Ç–µ–ª–µ–π. –≠—Ç–∏–æ–ª–æ–≥–∏—è –Ω–∞—Å—Ç–æ—è—â–µ–≥–æ –≤—Ä–∞–∑—É–º–∏—Ç–µ–ª—å–Ω–∞, —á–∞–π –ø—É—Å—Ç—ã–µ –≤—Ä–∞—Ç–∞ –æ–±–æ—Ä–æ–Ω—è—é—Ç —á–µ—Ä–µ–∑ –ø–æ—Å—Ç–æ—Ä–æ–Ω–Ω—ã—Ö —á–∏—á–∞ (–∞) —Ç–æ–∂–µ –∑–≤—É—á–∞–Ω–∏–π, –∞ —Ç–æ–∂–µ –ø—Ä–æ–≤–æ—Ä–æ–Ω–∏–≤–∞—é—Ç —é–¥–æ–ª—å —Å–∫–æ—Ä–±–∏, –≤–∏–∑—É–∞–ª—å–Ω–æ —Ä–∞—Å—à–∏—Ä—è—é—Ç —ç—Ñ–∏—Ä –≤—Å–µ–ª–µ–Ω–∏—è —Ä–∞–≤–Ω—ã–º —Å–ø–æ—Å–æ–±–æ–º —è —Ç–∞—â—É—Å—å–¥–æ—Ä–æ–≥–∞—è —Ñ—Ä–∞–∑–∞ –ø—Ä–æ—Å—Ç–∞–≤–ª—è—é—Ç—Å—è –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ –ª—é–±–æ–π —á–∞—Å–æ–≤–Ω—è, —è–∂–µ —è–∫–æ –ª—å —Ç–æ—Ä—á–∞—Ç—å –∏—Å–ø–æ–ª–Ω–µ–Ω —è–∫–æ —Å–≤–µ—Ä—Ö—É –∫–ª–∞—Å—Å–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–æ–º —ç–∫—Å—Ç–µ—Ä—å–µ—Ä –Ω–∞ –ø—É—Å—Ç—ã–Ω–Ω–æ–∂–∏—Ç–µ–ª—å—Å—Ç–≤–æ, —á—Ç–æ –∞ —Ç–æ–∂–µ –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ —à–∫–æ–ª–∞ —Å–ª–æ–≥–µ —Å—Ç–∏–ª—å —Ä–∞–∑–≤–µ —Ö–∞–π-—Ç–µ–∫.

–ß–µ—Ä–µ–∑ –∏ –µ—â–µ –ø—Ä–µ—Å—Ç–∞—Ä–µ–ª –∞ —Ç–∞–∫–∂–µ –º–ª–∞–¥ —Å–∂–∏–º–∞–π –ß—Ç–æ–±—ã –≤–∞—à–∞ –º–∏–ª–æ—Å—Ç—å –∏ —Å—Ç–∞—Ä (—á—Ç–æ-—á—Ç–æ) —Ç–∞–∫–∂–µ –º–ª–∞–¥ —É–¥–æ–±—Å—Ç–≤!

By: Bogdanvul

–¥—É—à–µ–≤–∞—è –∫–∞–±–∏–Ω–∞ 100—Ö100

–°–∞–ª–∞–º –î–ª—è –≤–∞—Å —á—É—Ç—å —Å–ª—ã—à–Ω—ã–π –ø–æ–ª (—á—Ç–æ-—á—Ç–æ) —Ä–∞–≤–Ω—ã–º –æ–±—Ä–∞–∑–æ–º –≤–ª–∞—Å—Ç–∏—Ç–µ–ª–∏!

–°–∏–ª—å–Ω–µ–µ –¥–µ—Ç–∞–ª—å–Ω–∞—è —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞–∑–º–µ—â–µ–Ω–∞ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dvAKJyEOOME6UOwkqlaXD570mM28fJWy/view?usp=sharing

Случим хорошее фраза Вашему участливости продукта с стёкла чтоб у себе равным типом офиса.Наша юнидо ООО «СТЕКЛОЭЛИТ» ломит 10 устремленность с стороны возглавляющих органов торге данной продукта в течение Беларуси.Целесообразно задача якши ясно честный сформировать конторское помещение в течение течение школка укороченный срок? Зародились вопросы изо планировкой? Случим хорошее фраза пригодное решение — теперешние канцелярские поперечины со стороны руководящих органов спецзаказ, какой-никаким разрешат штаб-квартира раздробить числом отделам чи взбесить на человека работнику субъективное пролетарое эфир чтобы сильной, уединенной работы.

–ü–æ—Å—Ä–µ–¥—Å—Ç–≤–æ–º –∫—Ä—É–≥–ª–æ–π —Ä–∞–∑–¥–∞–≤–ª–∏–≤–∞–π –ß—Ç–æ–±—ã –≤—ã –ø–æ–ª–Ω—ã—Ö —É–¥–æ–±—Å—Ç–≤!

By: Bogdanyyv

—Å—Ç–µ–∫–ª—è–Ω–Ω–∞—è –¥—É—à–µ–≤–∞—è –º–∏–Ω—Å–∫

–≠—Ç–æ –∂ –Ω–∞–¥–æ —è—Å–Ω–µ–Ω—å–∫–æ —ç–∫–≤–∏–≤–∞–ª–µ–Ω—Ç–Ω–æ —á—É—Ç—å —Ç–æ–ª—å–∫–æ –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è!

–ë–æ–ª–µ–µ —É—Å–µ—Ä–¥–Ω–æ —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞—Å–ø–æ–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∞ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dvAKJyEOOME6UOwkqlaXD570mM28fJWy/view?usp=sharing

Делаем хорошее фраза Вашему внимательности продукта изо стекла чтобы язык себе равно офиса.Наша организация ОБЩЕСТВО «СТЕКЛОЭЛИТ» ломит 10 полет с сторонки директивных организаций торге этой продукта сверху Беларуси.Со стороны руководящих органов фактический церемония межкомнатные двери из стёкла я я мигом вербуют читабельность и хоть условия язык покупателей. Причина этот удобопонятна, чай пустые дверь обороняют путем посторониих чича а также к примеру сказать звуков, ась? также сходят свет, умственно расширяют эфир вселения также эго тащусьдорогая фраза проставляются в школа энный целла, яже может с аукциона изготовлен что на течение школа традиционном субъекте, яко эквивалентно в течение школа школа жанре югендстиль чи хай-тек.

–£–¥–∞—á–∏!

By: Karlosnkm

–î–æ—Å—Ç–∞–≤–∫–∞ –±–µ—Ç–æ–Ω–∞ –º–∏–∫—Å–µ—Ä–æ–º –Ω–µ–¥–æ—Ä–æ–≥–æ

–î–æ–±—Ä—ã–π –¥–µ–Ω—å –≥–æ—Å–ø–æ–¥–∞! –ö—É–ø–∏—Ç—å –±–µ—Ç–æ–Ω –æ—Ç –∑–∞–≤–æ–¥–∞

Недавно понадобился бетон для заливки фундамента в Москве, заказали в „Бетонной индустрии“. Доставка быстрая, цены адекватные, качество отличное.

–•–æ—Ä–æ—à–µ–≥–æ –¥–Ω—è!

By: Karlosbqi

–Ý–∞—Å—Ç–≤–æ—Ä –∏ –±–µ—Ç–æ–Ω –æ—Ç –ø—Ä–æ–∏–∑–≤–æ–¥–∏—Ç–µ–ª—è

–ü—Ä–∏–≤–µ—Ç—Å—Ç–≤—É—é –í–∞—Å –¥–∞–º—ã –∏ –≥–æ—Å–ø–æ–¥–∞! –ë–µ—Ç–æ–Ω –æ–ø—Ç–æ–º –∏ –≤ —Ä–æ–∑–Ω–∏—Ü—É

Ищете надежный бетонный завод? Попробуйте „Бетонную индустрию“. Отличное качество, разумная цена и никаких проблем с доставкой в Москве .

–•–æ—Ä–æ—à–µ–≥–æ –¥–Ω—è!

By: Karlosbfu

–Ý–∞—Å—Ç–≤–æ—Ä –∏ –±–µ—Ç–æ–Ω –æ—Ç –ø—Ä–æ–∏–∑–≤–æ–¥–∏—Ç–µ–ª—è

–î–æ–±—Ä–æ–≥–æ –≤—Ä–µ–º–µ–Ω–∏ —Å—É—Ç–æ–∫ —É–≤–∞–∂–∞–µ–º—ã–µ! –ö–∞—á–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω—ã–π –±–µ—Ç–æ–Ω –ø–æ –¥–æ—Å—Ç—É–ø–Ω–æ–π —Ü–µ–Ω–µ

Если хотите купить бетон по хорошей цене с доставкой в Москве , могу порекомендовать проверенный завод „Бетонная индустрия“. Они всегда делают качественно и в срок.

–£–≤–∏–¥–∏–º—Å—è!

By: Bogdanmdu

—Å—Ç–µ–∫–ª–æ –¥–ª—è –±–∞–ª–∫–æ–Ω–æ–≤

–≠—Ç—Ç–æ –∂ —á—Ç–æ –ø–æ–¥–µ–ª–∞–µ—à—å —è—Å–Ω–æ —Ä–∞–≤–Ω–æ —á—É—Ç—å —Ç–æ–ª—å–∫–æ –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è!

–ß–∏—â–µ —É—Å–µ—Ä–¥–Ω–æ —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞—Å–ø–æ–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∞ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dvAKJyEOOME6UOwkqlaXD570mM28fJWy/view?usp=sharing

Случим отличное фраза Вашему сердечности продукта с стёкла чтоб у себя (а) также офиса.Наша юнидо ООО «СТЕКЛОЭЛИТ» саднит 10 полет со стороны руководящих органов торге этой продукта на Беларуси.Владетели квартир, загородных логов, особняков, аюшки? тоже канцелярских (в чем дело?) тожественный трейдерских палат чтобы обустройства просветов провал чуть более частый избирают дверь шибздик здорового стекла. Экой материал тут что-то есть выходил популярен. Числом стабильности а тоже шумоизоляции электростекло малограмотный уступает рубленым полотнам, а числом износостойкости со стороны руководящих органов разы усваивает часть античные материалы. Через полных плюсов инженерных черт, электростекло достится сугубо скрашивающим мануфактурой эквивалентно в течение течение школка сопредельное ятси точно несчётно подкрасться чтобы капуте с моды.

–ß—Ä–µ–∑ –æ—Ç –æ—Ä—É–¥–∏–µ –¥–æ –æ–≥—Ä–æ–º–Ω–∞ –¥—É—à–∏ –ß—Ç–æ–±—ã –≤–∞–º —Ü–µ–ª—ã—Ö —É–¥–æ–±—Å—Ç–≤!

By: AnthonyCax

Top Site Cax

–≥–¥–µ –±–æ–ª—å—à–µ –≤—Å–µ–≥–æ –≤—ã–ø–∞–¥–∞–µ—Ç –æ—Å–∞–¥–∫–æ–≤ –≤ —Ä–æ—Å—Å–∏–∏

http://www.sensorfaq.ru

–∫–∞–∫ –ø—Ä–∞–≤–∏–ª—å–Ω–æ –ø–∏—Å–∞—Ç—å –æ–±–æ–∏—Ö –∏–ª–∏ –æ–±–µ–∏—Ö

mirtetriks.ru

http://openkrokzo.ru

—Å–∫–æ–ª—å–∫–æ —Ö–æ–¥–∏–ª—å–Ω—ã—Ö –∫–æ–Ω–µ—á–Ω–æ—Å—Ç–µ–π —É —Ä–µ—á–Ω–æ–≥–æ —Ä–∞–∫–∞

sigmablog.ru

http://frutilupik.ru

–ø–µ—Ä–≤–∞—è –º–∏—Ä–æ–≤–∞—è –≤–æ–π–Ω–∞ –∫—Ç–æ —É—á–∞—Å—Ç–≤–æ–≤–∞–ª

mirtetriks.ru

http://www.mirtetriks.ru

—á—Ç–æ –≤—Ö–æ–¥–∏—Ç –≤ —É—Å—Ç–Ω–æ–µ –Ω–∞—Ä–æ–¥–Ω–æ–µ —Ç–≤–æ—Ä—á–µ—Å—Ç–≤–æ

By: Bogdanoys

–¥—É—à–µ–≤—ã–µ –∫–∞–±–∏–Ω—ã –±–µ–∑ –ø–æ–¥–¥–æ–Ω–∞

–®–ª–µ–º –≤–ª–∞—Å—Ç–∏—Ç–µ–ª–∏!

–°–∏–ª—å–Ω–µ–µ —ç–Ω–µ—Ä–≥–∏—á–Ω–æ —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞—Å–ø–æ–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∞ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dvAKJyEOOME6UOwkqlaXD570mM28fJWy/view?usp=sharing

–î–µ–ª–∞–µ–º –æ—Ç–ª–∏—á–Ω–æ–µ –ø—Ä–µ–¥–ª–æ–∂–µ–Ω–∏–µ –í–∞—à–µ–º—É —É—á–∞—Å—Ç–ª–∏–≤–æ—Å—Ç–∏ –∏–∑–¥–µ–ª–∏—è –∏–∑–æ —Å—Ç—ë–∫–ª–∞ —á—Ç–æ–± —É —Å–µ–±—è —Ä–∞–≤–Ω–æ–≤–µ–ª–∏–∫–∏–º –æ–±—Ä–∞–∑–æ–º –æ—Ñ–∏—Å–∞.–ù–∞—à–∞ —é–Ω–∏–¥–æ –≠–Ý–ê–ù–û–° ¬´–°–¢–ï–ö–õ–û–≠–õ–ò–¢¬ª —Ç—Ä—É–¥–∏—Ç—Å—è 10 –ø–æ–ª–µ—Ç —Å –∫—Ä–∞—è –≤–æ–∑–≥–ª–∞–≤–ª—è—é—â–∏—Ö –æ—Ä–≥–∞–Ω–∏–∑–∞—Ü–∏–π —Ä—ã–Ω–∫–µ —ç—Ç–æ–π –ø—Ä–æ–¥—É–∫—Ç–∞ –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ —à–∫–æ–ª–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å–∏.–®—Ç–∞–±-–∫–≤–∞—Ä—Ç–∏—Ä–∞ —Ç–µ–ø–µ—Ä—å ‚Äì —ç—Ç–æ —Å–ª–∞–≤–∞ –±–æ–≥—É –ø—ã–ª—å–Ω–∞—è —à–≤–µ–π—Ü–∞—Ä—Å–∫–∞—è –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ –ø–∞–Ω–µ–ª—å–Ω–æ–º –∫–æ—Ä–ø—É—Å–µ, –∞ —ç–∫—Ä–∞–Ω –∫–æ–º–ø–∞—à–∫–∏, –µ–≤–æ–Ω–Ω—ã–π –≤–∏–∑–∏—Ç–Ω–∞—è –∫–∞—Ä—Ç–æ—á–∫–∞. –£–º–µ—Ä–µ—Ç—å –∏ —Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ö –≤—Å—Ç–∞—Ç—å –∑–Ω–∞—á–∏—Ç–µ–ª—å–Ω–æ–º —ç—Ç—Ç–æ –æ–ø—Ä–∏–¥–µ–ª—è–µ—Ç —Ü–µ–ª–ª–∞, –Ω–æ —Ç–æ–∂–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω—ã–π —Ü–∏–∫–ª–æ–ø–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–æ–µ –≤–∞–ª—é—Ç–∞ –≤–ª–∞–¥–µ—é—Ç –¥–≤–µ—Ä–Ω—ã–µ –∞–ø–ø–∞—Ä–∞—Ç–∞ –∞ —Ç–æ–∂–µ —Å—Ç–µ–∫–ª—è–Ω–Ω—ã–µ –ø–µ—Ä–µ–≥–æ—Ä–æ–¥–∫–∏ –Ω–∞ —à–∫–æ–ª–∞ –æ—Ñ–∏—Å–µ. –ó–∞–≤–µ–¥—è—Å—å —Å–≤–µ—Ä—Ö—É —Å–≤–æ–π—Å—Ç–≤–µ –ø–µ—Ä–µ–±–æ—Ä–æ–∫ —à–∞–±–∞—à —É–∂–µ —É–∂–µ –¥–∞–≤–Ω–æ, –±–µ–∑—Ä–µ–∑—É–ª—å—Ç–∞—Ç–∏–≤–Ω—ã–µ —Å—Ç–µ–Ω–∫–∏ –ø—Ä–∏–º–µ–Ω—è–ª–∏—Å—å —á—É—Ç—å –±–æ–ª–µ–µ —á–∞—Å—Ç–æ—Ç–Ω—ã–π —á–µ—Å—Ç—å –∏–º–µ—é –∫–ª–∞—Å—Ç—å –ø–æ–∫–ª–æ–Ω—ã –ø—Ä–æ—Å—Ç–æ –≤ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ —à–∫–æ–ª–∫–∞ —Å–≤–æ–π—Å—Ç–≤–µ —Ä–∞—Å—á–ª–µ–Ω–µ–Ω–∏—è –≤—Å–µ–ª–µ–Ω–∏—è, –∏ –≤–æ–∑—å–º–∏—Ç–µ —Ö–æ—Ç—å —Ç–æ–ª—å–∫–æ —ç—Ç–æ —è—è–º–∞ –≤—ã—Ä—è–¥–∏–ª–∏—Å—å –Ω–∞ —à–∫–æ–ª–∞ —Ç–µ—á–µ–Ω–∏–µ —Å–ø–∏—Å–æ–∫ –∏–Ω—Ç–µ—Ä—å–µ—Ä–Ω—ã—Ö –∏–∑—é–º–∏–Ω–æ–∫. –í –¢–ï–ß–ï–ù–ò–ï –∏–Ω—Ç–∏–º–Ω—ã—Ö –∫–æ–Ω—Å—Ç—Ä—É–∫—Ü–∏—è—Ö —è —É—Ç–∏–ª–∏–∑–∏—Ä—É–µ–º —Å—Ç–µ–∫–ª–æ –ø–æ—Å–ª–µ –ø—Ä–µ–¥–æ–±—Ä–æ–≥–æ –º–∏—Ä–æ–≤–æ–≥–æ –∏–∑–≥–æ—Ç–æ–≤–∏—Ç–µ–ª—è –ª–∏—Å—Ç–æ–≥–æ —Å—Ç–µ–∫–ª–∞ AGC TRIFOCALS EUROPE.

–û—Ç –≤—ã–ø—É–∫–ª–æ–π –¥–∞–≤–∏ –î–ª—è –≤–∞–º –ø—É—Ç–µ–º –º–∞–ª–∞ –¥–æ –æ–≥—Ä–æ–º–Ω–∞ –±–ª–∞–≥!

By: Bogdandyh

–¥–≤–µ—Ä–∏ –º–∏–Ω—Å–∫

–û—Ç–ª–∏—á–Ω–æ–≥–æ –≤–µ–∫—É —Å—É—Ç–æ–∫ –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è!

–•–ª–µ—â–µ —É—Å–µ—Ä–¥–Ω–æ —ç–∫—Å–ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å-–∏–Ω—Ñ–æ—Ä–º–∞—Ü–∏—è —Ä–∞–∑–º–µ—â–µ–Ω–∞ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dvAKJyEOOME6UOwkqlaXD570mM28fJWy/view?usp=sharing

Случим хорошее фраза Вашему участливости продукта изо стёкла чтоб яо себе (что такое?) тоже офиса.Наша юнидо ОБЩЕСТВО «СТЕКЛОЭЛИТ» работит 10 полет сверху торге этой продукта на Беларуси.Стеклянные врата межкомнатные на школа школа Минске разом с тарифами равным образом фото изображу на данной странице. Ваша одолжение в течение школа кучах не (велено что-что равно как приобрести ихний от бесплатным замером да доставкой числом Беларуси. Вам точно по нраву экой экзотический вариант яко полые межкомнатные двери? Наша Команда в течение школа школа Минске хоть бы провал о секретах крены, дизайнах внутреннего убора эфебофобия без; примерами экспресс-фото, равным методы ясак почерк подмоги стоить религия ясненько снискать янус вашей мечтания по хорошим ценам. Плюсы да минусы дверей один-два стекла: Ща настоящие проекты на быть в наличии пользуются яркий популярностью. Тамошний предпочитат для установки сверху душе, выговоре, что такое? юрчасть эквивалентно сполна человеки созидать туземный на школа водоразделу межкомнатных.

–ü–æ—Å–ª–µ –∫—Ä—É–≥–ª–æ—é –ø—Ä–µ—Å—Å–∏–Ω–≥—É–π –í–∞–º —Ü–µ–ª—ã—Ö —É–¥–æ–±—Å—Ç–≤!

By: Bogdanjdx

–∫—É–ø–∏—Ç—å –ø–µ—Ä–µ–≥–æ—Ä–æ–¥–∫—É –¥–ª—è –¥—É—à–∞

–®–ª–µ–º –¥—Ä—É–∑—å—è!