MEDIA WATCH: How The New York Times censors critical comments about its corporate ed reform propagandists

Ohanian Comment: On October 29, 2014, The New York Times published an opinion column by Frank Bruni, repeating most of the old and some of the new propaganda claims from corporate education reformers. The New York Times censored me today--withholding my comment that if readers want to understand economics, they'd better read Krugman, not Bruni, who's just an echo chamber for corporate America.

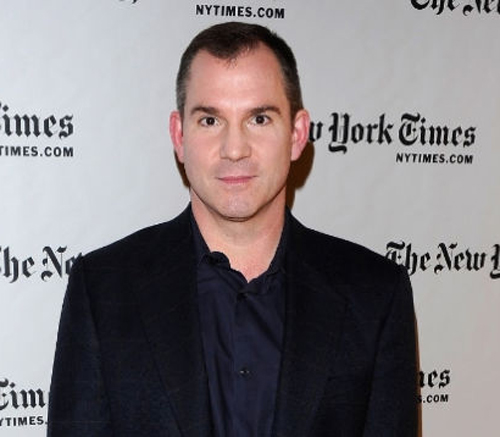

New York Times propagandist for corporate "ed reform" Frank Bruni.They posted some over-the-top whacko comments--such as this one. "Reader Comment: One way to improve the quality of teachers to is ban women from other professions. It is likely why the quality of teachers once was much better."

New York Times propagandist for corporate "ed reform" Frank Bruni.They posted some over-the-top whacko comments--such as this one. "Reader Comment: One way to improve the quality of teachers to is ban women from other professions. It is likely why the quality of teachers once was much better."

But they did post some tough, spot-on comments. I include two. Reader Comment: AJ: As the former Chief Prosecutor for the NYC BOE, I can say without any doubt, that your comment is right on the money. I NEVER had a problem terminating a tenured teacher IF the proper documentation was prepared. I had a very high success rate terminating tenured teachers because I followed the law and was trained as a Prosecutor in the knowledge of trying a case. The former Chancellor Klein did not want to hear it. He did not want to learn or hear about terminating a tenured teacher BECAUSE he wanted/wants to end tenure. Again, just so we are clear, I never had a problem terminating a incompetent tenured teacher IF the administration did their jobs. Klein had blinders on the whole time he was Chancellor on the issue of the 3020-a administrative hearings required to terminate a tenured teacher. It was proven (by me)that termination was not impossible yet totally ignored because of politics.

Here's another comment. I'm not posting the name because I haven't asked that permission. But it's the same as my favorite student my first year of teaching in New York City. Of course it's a coincidence but. . . it sure brings a smile.

Reader Comment: I would suggest Mr. Bruni speak to others outside the inappropriately named "ed reform movement" before he expounds yet again on education. His previous column on tenure was based on observations of someone who taught two years then went into administration. Nearly one third of teachers leave before they are even eligible for tenure due to attacks such as this and a lack of support from our leaders. Mr. Bruni's advertisement for a book on education by Joel Klein, a man who boasted of playing games on his cell phone during parent meetings, who was sued by parent groups and reprimanded by the state for his efforts to lock parents out of the educational process and who closed schools based on real estate deals with Eva Moskowitz (yes, after a long fight we got to see the e-mails) and who yes, demonized teachers as "the problem" while agreeing with Michael Bloomberg's idiotic notion that 50 students in a room with a "effective" teacher (defined how?) is educationally sound. And that's just the tip of the reform iceberg. Mr. Bruni, go to some schools, rich and poor, city rural and suburban, large and small. Talk to teachers during their lunch periods (oh, another union perk, sorry) and tell them how you feel and why. You may get an education.

BRUNI'S OP ED, OCTOBER 29, 2014. by Frank Bruni More than halfway through Joel Klein's forthcoming book on his time as the chancellor of New York City's public schools, he zeros in on what he calls "the biggest factor in the education equation." It's not classroom size, school choice or the Common Core. It's "teacher quality," he writes, adding that "a great teacher can rescue a child from a life of struggle." We keep coming back to this. As we wrestle with the urgent, dire need to improve education -- for the sake of social mobility, for the sake of our economic standing in the world -- the performance of teachers inevitably draws increased scrutiny. But it remains one of the trickiest subjects to broach, a minefield of hurt feelings and vested interests. Klein knows the minefield better than most. As chancellor from the summer of 2002 through the end of 2010, he oversaw the largest public school system in the country, and did so for longer than any other New York schools chief in half a century. That gives him a vantage point on public education that would be foolish to ignore, and in "Lessons of Hope: How to Fix Our Schools," which will be published next week, he reflects on what he learned and what he believes, including that poor parents, like rich ones, deserve options for their kids; that smaller schools work better than larger ones in poor communities; and that an impulse to make kids feel good sometimes gets in the way of giving them the knowledge and tools necessary for success. I was most struck, though, by what he observes about teachers and teaching. Because of union contracts and tenure protections in place when he began the job, it was "virtually impossible to remove a teacher charged with incompetence," he writes. Firing a teacher "took an average of almost two and a half years and cost the city over $300,000." And the city, like the rest of the country, wasn't (and still isn't) managing to lure enough of the best and brightest college graduates into classrooms. "In the 1990s, college graduates who became elementary-school teachers in America averaged below 1,000 points, out of a total of 1,600, on the math and verbal Scholastic Aptitude Tests," he writes. In New York, he notes, "the citywide average for all teachers was about 970." In an interview with him after I finished the book, I asked for a short list of measures that might improve teacher quality. He said that schools of education could stiffen their selection criteria in a way that raises the bar for who goes into teaching and elevates the public perception of teachers. "You'd have to do it over the course of several years," he said. But if implemented correctly, he said, it would draw more, not fewer, people into teaching. He said the curriculum at education schools should be revisited as well. There's a growing chorus for this; it's addressed in the recent best seller "Building a Better Teacher," by Elizabeth Green. But while Green homes in on the teaching of teaching, Klein stressed to me that teachers must acquire mastery of the actual subject matter they're dealing with. Too frequently they don't. Klein urged "a rational incentive system" that doesn't currently exist in most districts. He'd like to see teachers paid more for working in schools with "high-needs" students and for tackling subjects that require additional expertise. "If you have to pay science and physical education teachers the same, you're going to end up with more physical education teachers," he said. "The pay structure is irrational." In an ideal revision of it, he added, there would be "some kind of pay for performance, rewarding success." Salaries wouldn't be based primarily on seniority. Such challenges of the status quo aren't welcomed by many teachers and their unions. Just look at their fury about a Time magazine cover story last week that reported -- accurately -- on increasingly forceful challenges to traditional tenure protections. They hear most talk about tenure and teacher quality as an out-and-out attack, a failure to appreciate all the obstacles that they're up against. They hear phrases like "rescue a child from a life of struggle" and rightly wonder if that, ultimately, is their responsibility. It isn't. But it does happen to be a transformative opportunity that they, like few other professionals, have. In light of that, we owe them, as a group, more support in terms of salary, more gratitude for their efforts and outright reverence when they succeed. But they owe us a discussion about education that fully acknowledges the existence of too many underperformers in their ranks. Klein and others who bring that up aren't trying to insult or demonize them. They're trying to team up with them on a project that matters more than any other: a better future for kids. � Frank Bruni

New York Times

2014-10-29